Early Central European Orientalists in Search of Texts for Studies

Insights from Johann Ernst Gerhard’s Collection

The invention of printing with movable type in the mid fifteenth century in Mainz led to an unprecedented dissemination of books in the Germanic and Romance language areas of Europe in the following decades. In contrast, a parallel development in the Near East is first recognizable in the eighteenth century due to an amalgamation of lingual, religious, cultural, and social factors. Although the necessary technical knowledge existed, a market for printed books was initially missing in the Levant. The increasing interest of sixteenth and seventeenth-century scholars in oriental language raises the question of how early orientalists gained access to writings for their philological studies.

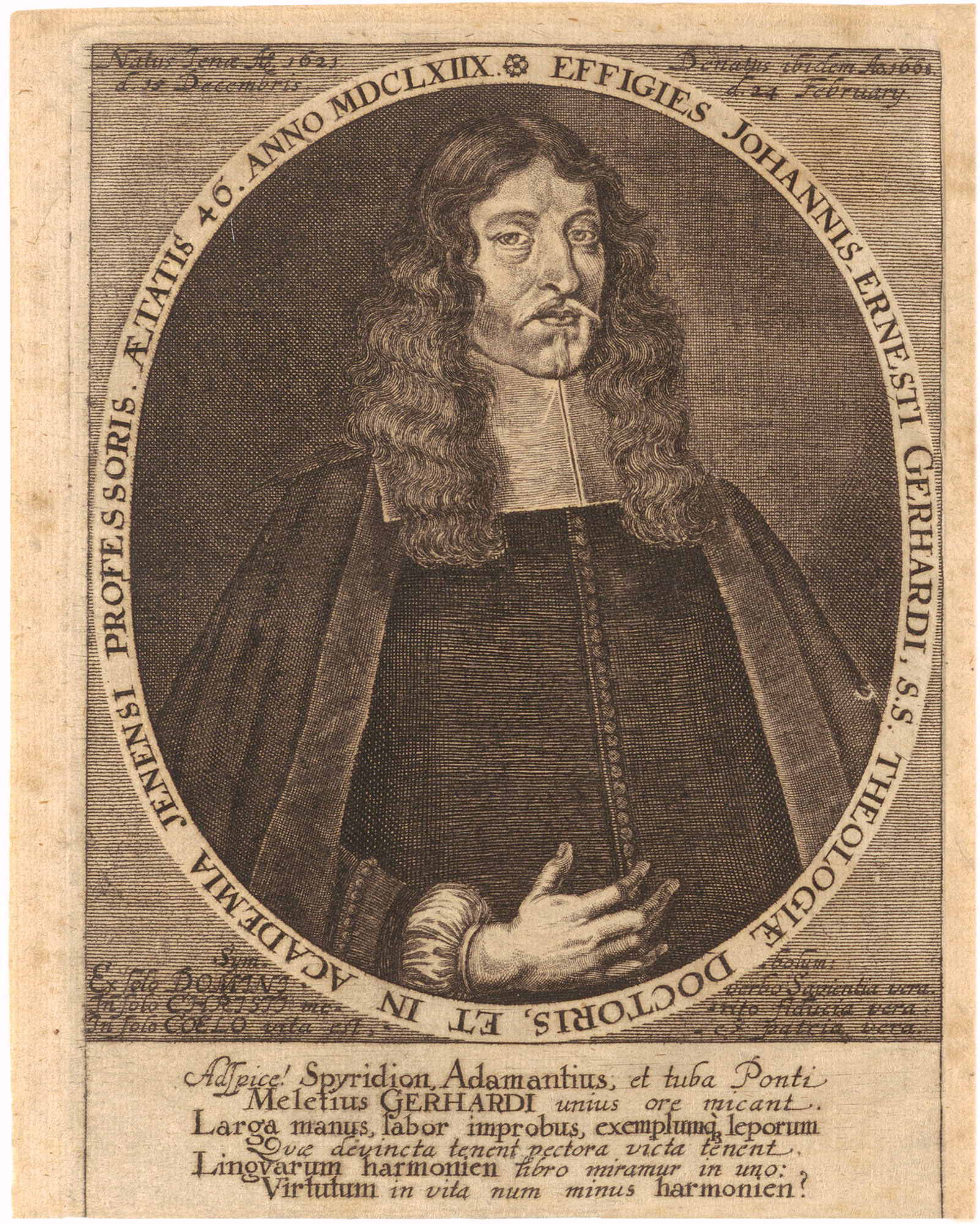

The Bibliotheca Gerhardina, one of the most significant scholarly libraries in early modern Germany, affords revealing insights into this question. Today, the greater part of this collection is located at the Gotha Research Library. Duke Frederick I of Sax-Gotha-Altenburg (1646–1691) acquired it in 1678 for the court library at the Friedenstein Palace. It was founded and vigorously expanded by the Lutheran theology professors at the University of Jena Johann Gerhard (1582–1637) und Johann Ernst Gerhard (1621–1668; fig. 1), father and son. The latter was one of the early orientalists in Central Germany. For this reason, he had a special interest in collecting Orientalia.

Notwithstanding, Orientalia formed a very small portion of the collection. Excluding grammars, lexica, thesauri, and other philological compendia as well as all books related to the Hebrew language that had established itself among European scholars already in the sixteenth century, merely 26 publications with writings in various oriental languages can be identified. That is less than half a percent of the 6,000 prints in the Bibliotheca Gerhardina. Half of these are partial editions of the Bible in Ethiopic, Syriac, and Arabic, one sixth excerpts from the Koran in Arabic, and one fifth various religious writings in Arabic, Ethiopic, Persian, and Armenian. Just four prints contain secular writings, including poems, sayings, and pre-Islamic fables in Arabic as well es a Turkish dialog between a Christian merchant and an Ottoman in Istanbul. This dialog, written by the erstwhile prisoner of the Ottomans, Bartolomej Đurđević (1506–1566), and published in a compendium on Turkish culture in Leiden in 1558, was represented in the Bibliotheca Gerhardina just as a handwritten copy. Interestingly, Johann Gerhard had made the copy in 1596 as a thirteen-year-old student at the Latin school in Quedlinburg.

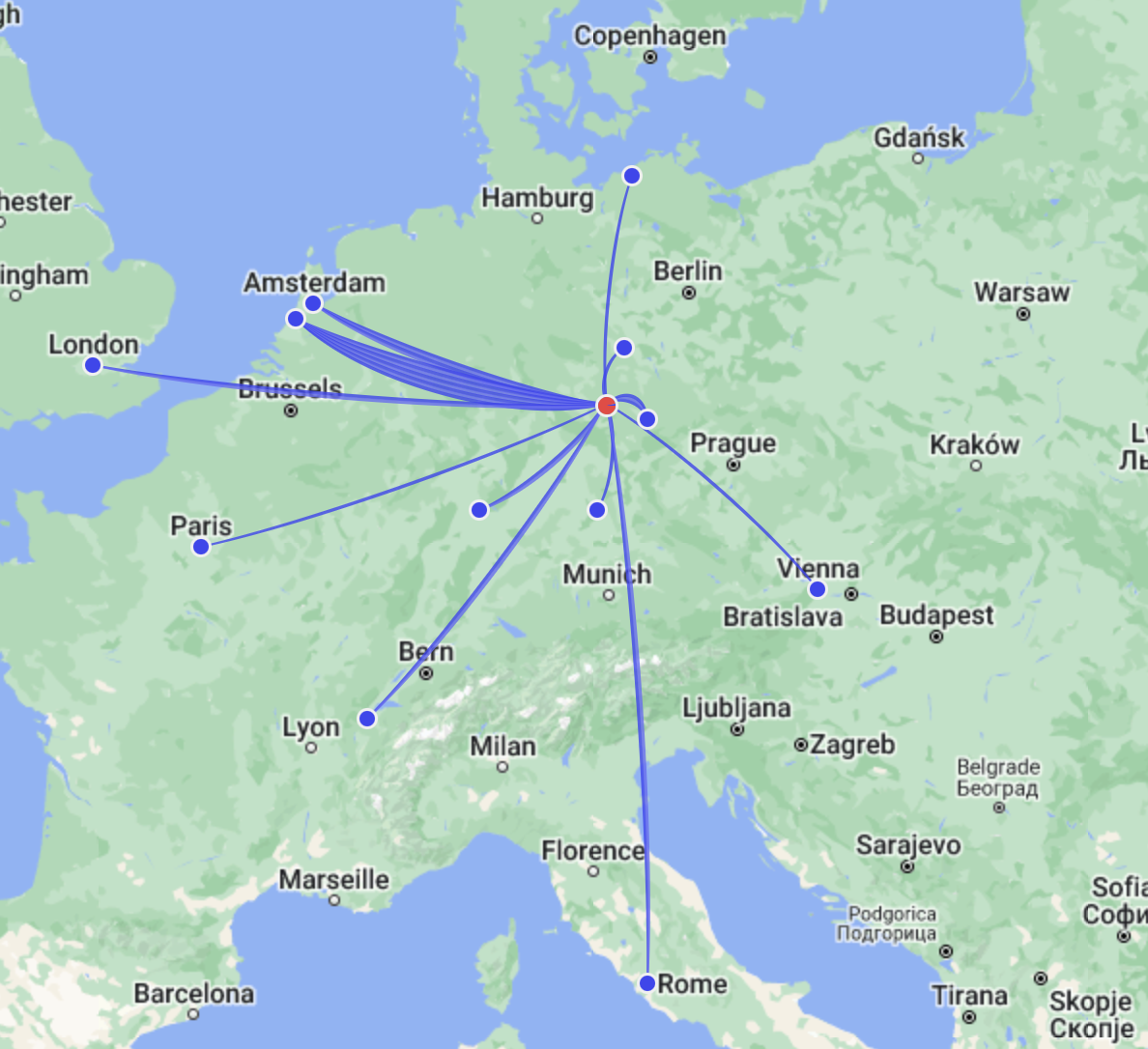

Fig. 2: Geographic visualisation of places where oriental writings in der Bibliotheca Gerhardina were printed.

Translations of the Bible and Arabic editions of the Koran made it possible for European scholars to gain a deeper understanding of the holy scriptures and at the same time to arm themselves for interreligious controversies. The primary purpose of some prints was to facilitate Christian missions. Among these were the depictions of the life of Christ and the Apostle Peter – the first pope from a Roman perspective – that the Spanish Jesuit Jerome Xavier (1549–1617) on the subcontinent of India at the court of the mogul Akbar (1542–1605) had composed in Persian and also an Armenian translation of the Doctrina Christiana, published by the Florentine cardinal Robert Bellarmin (1542–1621). This collection profile clearly shows that studies of oriental languages in Europe in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries were driven primarily by religious motives and secondarily by economic, diplomatic, and cultural interests.

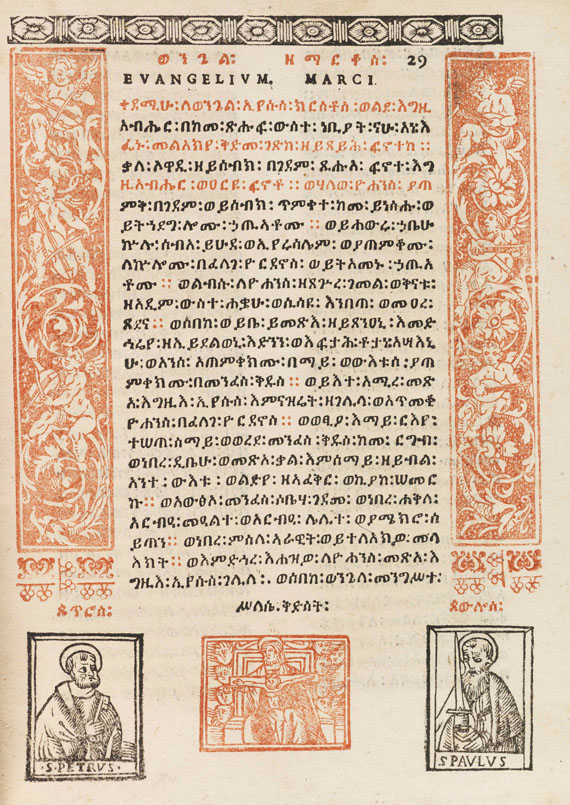

All 26 prints appeared in European publishing houses (fig. 2). One third alone was published in Leiden. Leiden became the printing center of oriental writings through the press with Hebrew, Arabic, Syriac, Ethiopian, and Turkish type founded by Thomas Erpenius (1584–1624; fig. 3). An Arabic translation of the New Testament and the Pentateuch or Torah – the first print of the five books of Moses in Arabic type – as well as a collection of sayings could be found from Erpenius’ press in the Bibliotheca Gerhardina. The Gerhards also had a Syriac edition of the Apocalypse that Erpenius’ successor Louis de Dieu (1590–1642) had published. The print was considered a sensation at its time in the Republic of Letters since the Ethiopic version of this last book of the Bible had remained unknown for centuries. Prints from other European metropoles, such as Rome, Amsterdam, London, Paris, and Vienna also represent milestones in the printing history of oriental writings and translations. Especially noteworthy is the first translation of the New Testament in Ethiopic, the oldest oriental print in the Bibliotheca Gerhardina, published in 1548 (fig. 4). It was the product of a joint effort of three monks, who were forced to flee the Empire of Abyssinia and who had found refuge in Rome.

Fig. 4: First page of the gospel of Mark in an Ethiopic translation of the New Testament, Rome 1548.

Other Arabic and Syriac prints in the Bibliotheca Gerhardina appeared in smaller Central European towns. These included works by Johann Ernst Gerhard’s language professors in Jena and Altdorf, Johann Michael Dilherr (1604–1669) and Theodor Hackspann (1607–1659), and by two German gymnasium teachers. In the newly founded press at the Köthen court, the local gymnasium teacher for oriental languages, Martin Trost (1588–1636), published a Syriac edition of the New Testament in 1621, whereas Johann Zechendorff (1508–1662) made four suras of the Koran and the Lord’s Prayer in Arabic-Latin editions available for lessons in the Zwickau gymnasium in the following decades.

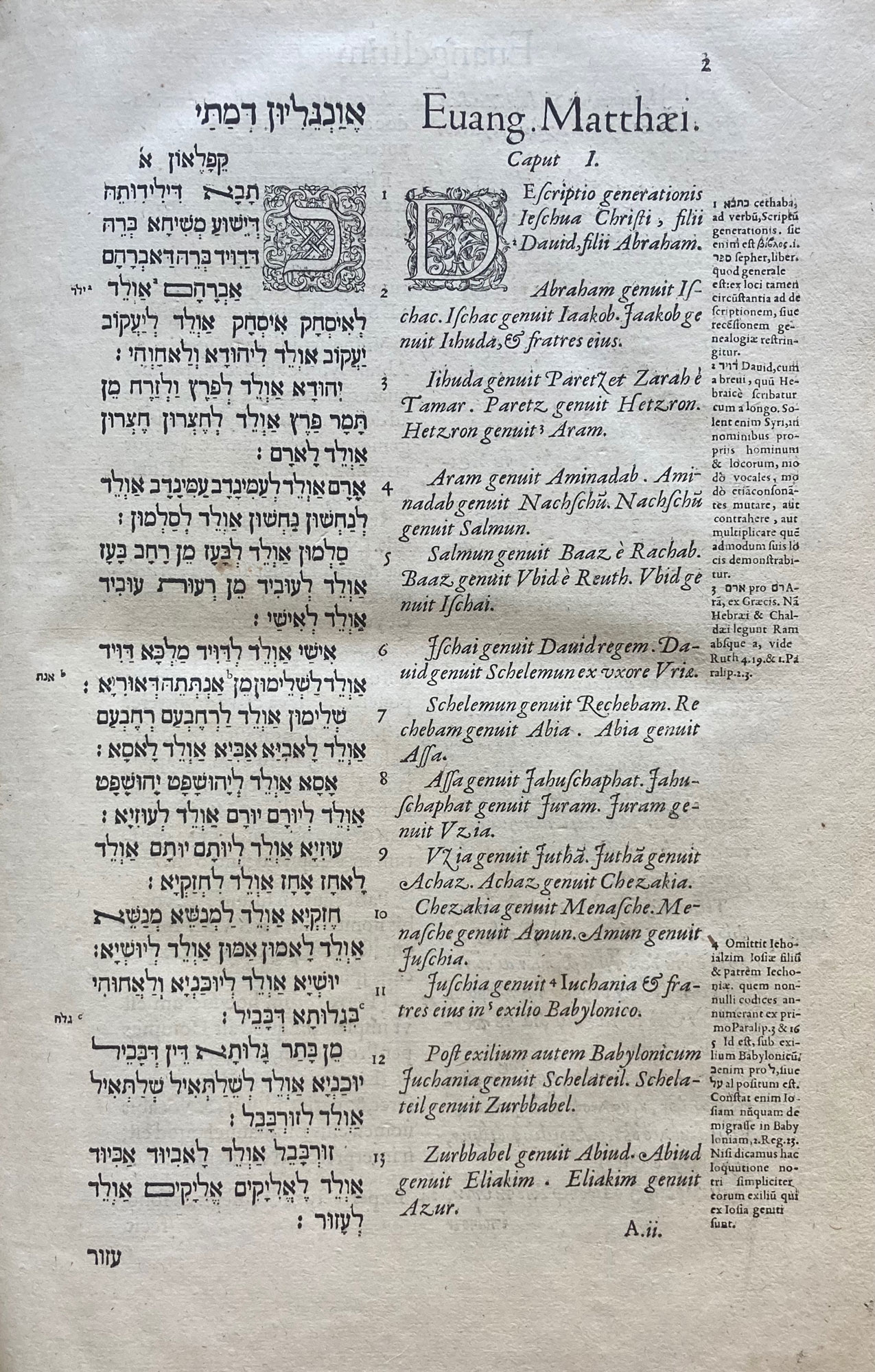

Simply producing and acquiring the appropriate type posed a special challenge in this early period that had to be overcome if one wanted to make oriental writings accessible to broad circles through print. They required a considerable financial investment. For example, as Immanuel Tremmelius (1510–1580), a Jewish convert to the Reformed faith, published a Greek-Latin edition of the New Testament with a Syriac interpretation in Geneva in 1569 he lacked Syriac type. He solved this problem by reproducing the Syriac text phonetically in Hebrew type (fig. 5). Zechendorff also had Arabic texts printed in Hebrew type. In other cases, he had full-page woodcuts or copperplate engraving made to present the Arabic texts in their appropriate alphabet. This was, however, a costly and time-consuming process.

Fig. 5: Immanuel Tremmelius: Syriac interpretation of the gospel of Matthew with Hebrew type, Geneva 1569.

Turning one’s attention to the 200 manuscripts in the Bibliotheca Gerhardina, it becomes readily apparent that the percentage of Orientalia, comprising almost 20 volumes, is considerably higher: nearly ten percent compared to less than half a percent. In addition, the diversity is much broader. Besides suras and commentaries on the Koran, the collection includes prayers, poems, legal texts, and a mirror for princes in Arabic, tales and medical writings in Turkish, as well as a chronicle of kings and a puzzle book in Persian. Half of the manuscripts were once part of Daniel Schwenter’s (1585–1636; fig. 6) library. Schwenter was professor for Arabic at the University of Altdorf near Nuremberg and died in 1636. As chance would have it, Gerhard studied in Altdorf at the beginning of the 1640s as Schwenter’s manuscripts were available for purchase. How Schwenter himself obtained these volumes during his lifetime is largely unknown. In Altdorf, where Gerhard began to learn Ethiopian, he also had access to a prayer book with apotropaic texts in this language at the university library. He made a copy for himself by hand. In later years, Gerhard received three manuscripts as gifts due to his reputation as an orientalist. Two were Arabic volumes that had come into the possession of the Ödenburg (today Sopron) lawyer István Vitnyédy (1612–1670) after the siege and plundering of Pécs by the Habsburgs in 1664. The third was a pilgrim souvenir in Arabic that the Ödenburg pastor and court preacher Matthias Lang (1624–1682) had given to Gerhard. These examples clearly show that well into the seventeenth century favorable coincidences played a significant role for those striving to build up oriental manuscript collections in the German Empire since it did not have strong trade connections to the Near East as did Holland, England and Italy. Thus, the existing market did not yet make it possible to systematically acquire Orientalia.

For the conditions of his time and the environment in which he worked, Johann Ernst Gerhard built up an impressive collection of prints and manuscripts for his oriental studies over three decades. The most important prints that he could acquire were published in metropoles outside of the empire. In some cases, they were produced by refugees from the Near East who brought their knowledge to Europe and disseminated it through prints. Europeans who published books in languages such as Arabic, Syriac, and Ethiopic, represented various Christian churches, including the Catholic, Lutheran, Reformed, and Anglican Church. Interest in oriental studies can therefore be understood as a phenomenon transcending confessional boundaries. Through networks of scholars, trade, missions, and war oriental manuscripts came into circulation. Nevertheless, they remained so rare in Gerhard’s time that they could seldomly be acquired in antique shops and auction houses. Instead, the manuscript collection of the Jena theologian and orientalist Johann Ernst Gerhard arose through the inheritance from his father, occasional purchasing opportunities, the making of handwritten copies, and gifts. The composition of oriental collections in other seventeenth-century Central European scholarly libraries was with exception of the holy scriptures also largely arbitrary.

Daniel Gehrt

Dr. Daniel Gehrt is a historian and research associate for cataloging Early Modern manuscripts at the Gotha Research Library

Primary source

- Digital images of the contemporary catalog of the Bibliotheca Gerhardina (Gotha Research Library, Chart. A 605) in the “Digitalen Historischen Bibliothek Erfurt/Gotha.” URL: https://dhb.thulb.uni-jena.de/receive/ufb_cbu_00042483

Secondary sources

- Paul Babinski: The Formation of German Islamic Manuscript Collections in the Seventeenth Century, in: Sabine Mangold-Will, Christoph Rauch, and Siegfried Schmitt (eds.): Sammler – Bibliothekare – Forscher: Zur Geschichte der orientalischen Sammlungen an der Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin. Frankfurt am Main 2022, pp. 19–44.

- Paul Babinski, Jan Loop, and Asaph Ben-Tov (eds.): The Turkish Wars and the Study of Islam in Early Modern Europe: Sonderausgabe des Journals: Erudition and the Republic of Letters 9/3 (2024).

- Lutz Berger: Zur Problematik der späten Einführung des Buchdrucks in der islamischen Welt, in: Ulrich Marzolph (ed.): Das gedruckte Buch im Vorderen Orient. Dortmund 2002, pp. 15–28.

- Daniel Gehrt and Hendrikje Carius (eds.): Katalog der Handschriften aus den Nachlässen der Theologen Johann Gerhard (1582–1637) und Johann Ernst Gerhard (1621–1668): Aus den Sammlungen der Herzog von Sachsen-Coburg und Gotha’schen Stiftung für Kunst und Wissenschaft. Wiesbaden 2016, esp. pp. 502–520.

- Feras Krimsti (ed.): Der Orient in Gotha. Katalog zur Ausstellung der Forschungsbibliothek Gotha auf Schloss Friedenstein vom 8. September bis 3. November 2024. Gotha 2024, esp. the editor’s introduction and the contributions by Hendrikje Carius (no. 3), Daniel Haas (no. 12), Stefan Hanß (no. 2), and Christoph Rauch (no. 28).

- Johann Anselm Steiger (ed.): Bibliotheca Gerhardina: Rekonstruktion der Gelehrten- und Leihbibliothek Johann Gerhards (1582–1637) und seines Sohnes Johann Ernst Gerhard (1621–1668), 2 Teilbände. Stuttgart-Bad Cannstatt 2002.

- Asaph Ben-Tov: Johann Zechendorff (1580–1662) and Arabic Studies at Zwickau’s Latin School, in: Jan Loop, Alastair Hammilton, and Charles Burnett (eds.): The Teaching and Learning of Arabic in Early Modern Europe. Leiden/Boston 2017, pp. 57–92.

- Asaph Ben-Tov: Johann Ernst Gerhard (1621–1668): The Life and Work of Seventeenth-Century Orientalist. Leiden/Boston 2021.

Web

- Catalog descriptions of the oriental manuscripts in the Bibliotheca Gerhardina in the union catalog “Kalliope” and the portal “Qalamos.” URL: https://kalliope-verbund.info URL: https://qalamos.net

Picture credits

- Christian Romstet: Portrait of Johann Ernst Gerhard, 1668. Copperplate engraving. Gotha Research Library, LP E 8° III, 18 (23), before the title page.

- Geographic visualisation of places where oriental writings in der Bibliotheca Gerhardina were printed. Produced with the assistance of Nodegoat. Map data ©2024 Google.

- Portrait of Thomas Erpenius, 1625. Copperplate engraving. Reijksmuseum Amsterdam, RP-P-1906-1568 (CC0).

- First page of the gospel of Mark in an Ethiopic translation of the New Testament, Rome 1548. © Ketterer Kunst GmbH und Co. KG. Link (Accessed: 29.10.2024)

- Immanuel Tremmelius: Syriac interpretation of the gospel of Matthew with Hebrew type, Geneva 1569. Gotha Research Library, Theol 2° 4/1, p. 2.

- Lucas Kilian: Portrait of Daniel Schwenter, 1623. Copperplate engraving. Gotha Research Library, Illf X 4° 208 (2), fol. (:) 8v.