A Refutation of Muslims, Jews, and “Heretical” Christians, printed in Arabic: A Catholic Missionary at Work in 17th Century Aleppo

In 1687, a desperate plea reached the Vatican from Ottoman Aleppo. The French Consul Laurent d’Arvieux (1635–1702) wrote to the Propaganda Fide “that the whole Christian community of Aleppo would be grateful if you would deliver it from F. Justinien, as an absolute necessity.” He suggested to the Vatican to send the Capuchin missionary to Baghdad, Basra, Isfahan or elsewhere – locations that were sufficiently removed to put a comfortable distance between the missionary and Aleppo’s Christians.

The missionary in question, Justinien de Neuvy, born Michel Febvre (also known as Michele Febure, or Michel Fébure) had been active for more than twenty years in Aleppo, roughly from 1664 to 1687. It is not obvious why the Christian community eventually tried to get rid of him and why the Consul, who was supposed to be his protector, adopted the same position. It is likely that Michel Febvre’s missionary zeal made him a liability for Aleppo’s Christians. This is also suggested by a unique printed book in Arabic, a copy of which has recently been acquired by the Gotha Research Library – its author was none other than Michel Febvre.

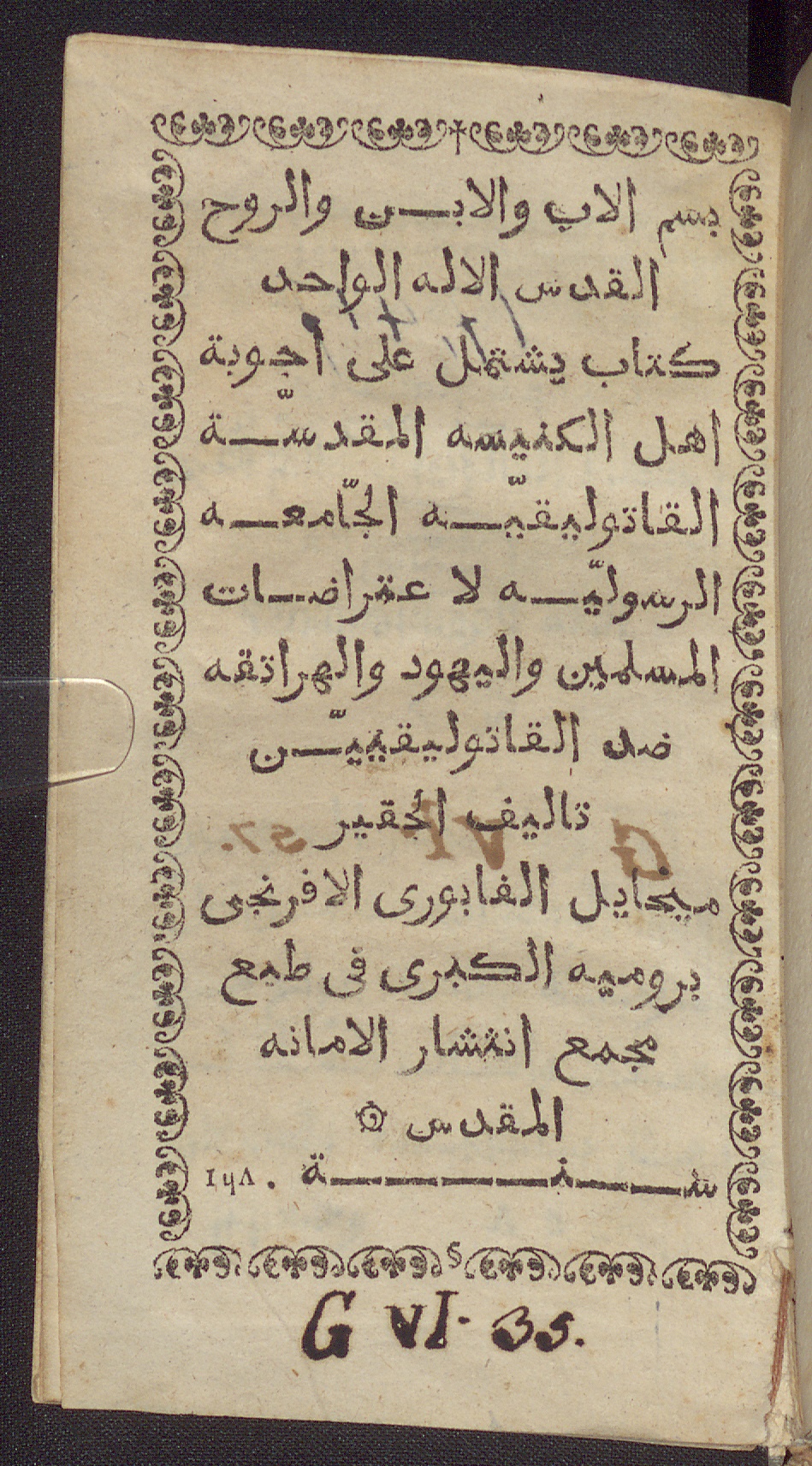

Printed in Arabic, the work bears the title The book comprising answers of the people of the Holy Catholic Universal Apostolic Church to the objections of the Muslims, Jews and heretics who oppose the Catholics. A refutation of Muslims, Jews, and “heretical” (i.e., non-Catholic) Christians, it was printed for the first time in Latin by the Propaganda Fide press in Rome in 1679; the Arabic version followed in 1680. The fictitious polemical dialogue between Christians and Muslims has a long history, dating back at least to the Abbasid era, and Catholic missionaries from Europe had revived it for their purposes in Ottoman times. However, a work in Arabic containing a refutation of Islam was unheard of, and could have come at high costs for Aleppo’s Christians.

Aleppo in the seventeenth century was not only a commercial hub. Because of the prosperity of the Christian community, it was also an important religious centre that attracted Catholic missionaries who primarily sought to rectify the beliefs of Arabic-speaking Christians. In 1673, Sultan Mehmed IV (1642–1693) guaranteed the safety of French missionaries on Ottoman soil, but long before this, all major Catholic congregations were already active in Aleppo: Jesuits, Franciscans, Capuchins and Carmelites. In this milieu, the Capuchin missionary Michel Febvre went far beyond trying to win Christians over to Catholicism: in 1668, for example, he made attempts to convert the Yazidis who lived one day’s journey from Aleppo. These attempts failed, but they demonstrate that Michel Febvre was willing to go above and beyond ordinary missionary activity. He might have been willing to convert Muslims to Catholicism.

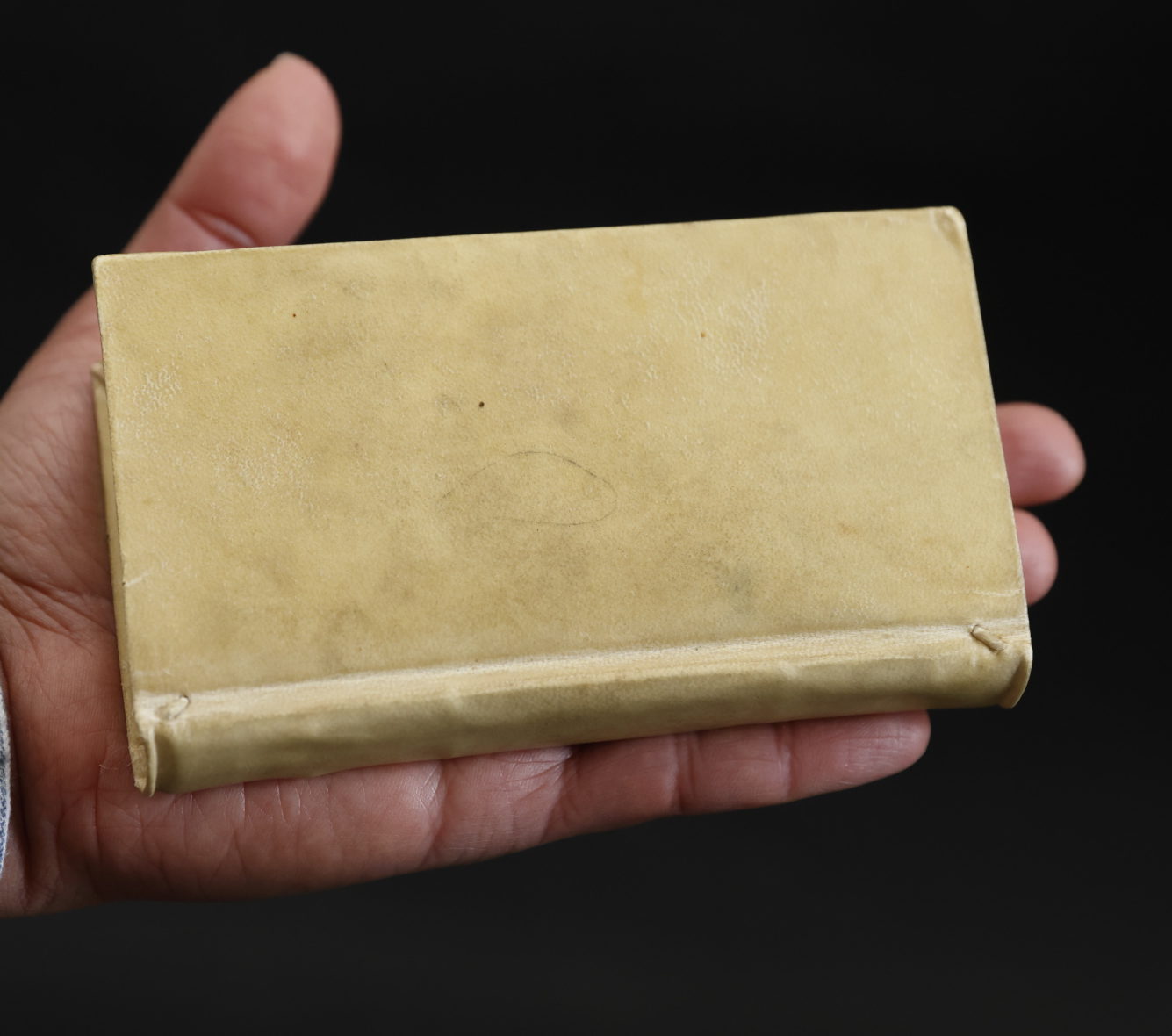

The secrecy with which the printed refutation in Arabic would have had to be used is suggested by its very small format: it was pocket-sized, to be tucked away and hidden swiftly. The work is divided into three main parts the first of which is the one dedicated to Islam. It is short (pp. 9–44) compared to the rest of the book, constituted by a part directed against the Jews (pp. 49–87) and, above all, against “heretical” Christians (pp. 88–286). The compactness of the first part is deceiving. Polemical works by Christians against Christians were abundant and remained by and large without political consequences under Ottoman rule, but the same could not be said about works by Christians against Muslims.

The topics addressed in the refutation of Islam seem rather innocuous at first glance. They are classical topics known from medieval polemical dialogues: the Trinity, the divinity of Jesus, the divine sonship, and icon worship. However, besides such well-known topics, Michel Febvre also attacks Muḥammad and the Qur’an in relatively explicit terms. For example, he raises a potential question by “some Muslim”: “Why do they [i.e., the Christians] not believe in the message of the Prophet Muḥammad?… And why do they not accept his law as it was revealed in the texts of the Qur’an?” (p. 26) To this he responds, “Christians cannot accept Muḥammad the Hashimite, and they cannot act by the law of the Qur’an, because the law of the Messiah cannot be abolished: the servant cannot rise above his master…” – the servant meaning Muḥammad, the master meaning Jesus (p. 31). This is an answer that would certainly have scandalized anyone who read it in seventeenth-century Aleppo.

We do not know whether such ideas were articulated in conversation among Aleppo’s Christians, or among Christians in other parts of the Ottoman Empire. Nor do we know who used the printed refutation, and on which occasions. We cannot even guess how widely it circulated; today only two copies are preserved in libraries worldwide besides the one in Gotha, namely in Yale and in Paris. We may plausibly assume that such a work, printed in Arabic for everyone to read, would have caused a considerable degree of unease and fear among Michel Febvre’s Christian coreligionists. Perhaps enough for him to be sent away? The refutation is not only important as a testimony to the early history of Arabic printing, it also sheds new light on Catholic missionary activity in the Near East and the impact of the Counter Reformation outside of Europe.

Feras Krimsti

Feras Krimsti is researcher and curator for the oriental manuscript collection at the Gotha Research Library.

Illustrations

- A Franciscan friar of the Capuchin order. Engravement, François de Poilly (1623–1693). Image in: Pierre Hélyot, Histoire des ordres monastiques, religieux et militaires… Paris: Jean-Baptiste Coignard, 1714, Vol. 7, after p. 170. Image credit: Emory University, Pitts Theology Library Digital Image Archive.

- Title page of Michel Febvre’s Kitāb yashtamilu ʿalā ajwibat ahl al-kanīsa… (Arabic print, Propaganda Fide, 1680). Gotha Research Library of the University of Erfurt, Th 8° 07324, title page.

- View of the city of Aleppo, around 1700. (Image in: Henry Maundrell: A Journey from Aleppo to Jerusalem at Easter, A.D. 1697. Oxford: Printed at the Theatre, 1749.) Image credit: Wellcome Collection.

- Michel Febvre’s 1680 refutation in Arabic is pocket-sized: 14 x 7,5 x 2 cm. Gotha Research Library of the University of Erfurt, Th 8° 07324, cover

Literature

- Heyberger, Bernard: Polemic Dialogues between Christians and Muslims in the Seventeenth Century, in: Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 55 (2012), pp. 495–516.

- Heyberger, Bernard: Justinien de Neuvy, dit Michel Febvre, in: Christian-Muslim Relations. A Bibliographical History. Vol. 9, Western and Southern Europe (1600–1700), ed. David Thomas and John Chesworth, Brill: Leiden/Boston, 2017, pp. 579–588.