From an Inspiring Turning Point to a Life’s Work: Ferdinand Wüstenfeld’s Oriental Studies in Gotha

In the late autumn of 1832, a young scholar from Göttingen embarked on a journey to Gotha. Ferdinand Wüstenfeld (1808–1899, fig. 1), who had recently completed his habilitation and was still at the beginning of his academic career, set out to the renowned ducal library in search of Arabic manuscripts, which until then had been almost unknown in Europe. Little did he know that this trip would change his life forever. It laid the foundations for his career as one of the most important German orientalists of the 19th century.

Wüstenfeld’s life’s work is closely tied to the rise of oriental studies in Europe in the 19th century, which led to intensive efforts in editing Arabic sources.1Cf. Mangold 2004. Although he never travelled to the Arab world, he became a key figure in the systematic editing of Arabic manuscripts.2On Wüstenfeld’s work, see, among others, Dugat 1870, pp. 273–287; Wüstenfeld 1890; Wellhausen 1910; Fück 1955, pp. 193f.; Stein 1997, pp. 231f.; Görgün 2013.

What inspired Ferdinand Wüstenfeld to dedicate himself to oriental languages? In his autobiographical notes, he describes the early beginnings of his passion. His father, a sugar manufacturer from Hannover Münden, attached great importance to a thorough Hebrew education to prepare his son for theological studies. One evening, Wüstenfeld recalls, his father returned from the club and suggested to him: “Today, there was talk of Professor Horn, who is said to be very learned […] and is proficient in Hebrew, Arabic, and Syriac. Why don’t you ask him if he would be willing to give you lessons?”3“Du, da war heute von dem Professor Horn die Rede, daß er sehr gelehrt sei […] und auch Hebräisch, Arabisch und Syrisch verstünde. Willst du ihn mal fragen, ob er dir darin Stunden geben wolle?“ Wüstenfeld 1890–1939, pp. 60f./p. 25. (The first page number refers to the manuscript, the second to the transcription of the memoirs). This offhand remark marked the beginning of Wüstenfeld’s lifelong fascination with oriental languages. However, he initially learned to write “only from the rigid fonts of printed books […] as I had no access to original Arabic manuscripts, which I only came across years later.“4“bloß nach den steifen Typen der gedruckten Bücher […], da mir keine Originale Arabischer Handschriften zugänglich waren, die ich erst nach einigen Jahren zu sehen bekam.“ Wüstenfeld 1890–1939, pp. 60f./p. 25. During his theological studies, he found himself “particularly captivated by Arabic with its incomparably rich and still largely undiscovered literature.”5“besonders das Arabische mit seiner unvergleichlich reichhaltigen noch so wenig bekannten Literatur“, Wüstenfeld 1890–1939, p. 87/p. 35. Faced with the immense quantity of unexplored Arabic works, he abandoned the prospect of becoming a pastor and focused instead on studying oriental languages in Göttingen and Berlin.

From 1838 as university librarian in Göttingen, later as associate professor and from 1856 as full professor of oriental languages, he devoted himself above all to the publication of important Arabic sources, which he thus made accessible to European researchers for the first time. Among other achievements, he edited critical historical, biographical, and geographical works of classical Arabic literature, published encyclopaedias, and developed various tools for oriental studies – including genealogical tables of Arab tribes and families as well as guides to the Islamic calendar. Notably, he published the most important Arabic-language source text on the life of Muhammad, authored by Ibn Hishām.6Wüstenfeld 1858/59.

Wüstenfeld relied on manuscripts preserved in European libraries or private collections. Among these, the oriental manuscript collection of the Ducal Library in Gotha – recognised as the largest and most significant repository of Arabic manuscripts in the German-speaking world – proved to be a cornerstone for his editorial achievements. His close collaboration with the library director Friedrich Jacobs (1764–1847), as well as with the orientalists and librarians Johann Heinrich Möller (1792–1867) and Wilhelm Pertsch (1832–1899), fostered a rich intellectual exchange. Their correspondence reveals a shared commitment to advancing the study of Arabic sources through a rigorous dialogue on research priorities and publication strategies.7See, among others, the correspondence preserved in the FB Gotha, the BSB Munich, the SBB-PK Berlin and the SUB Göttingen.

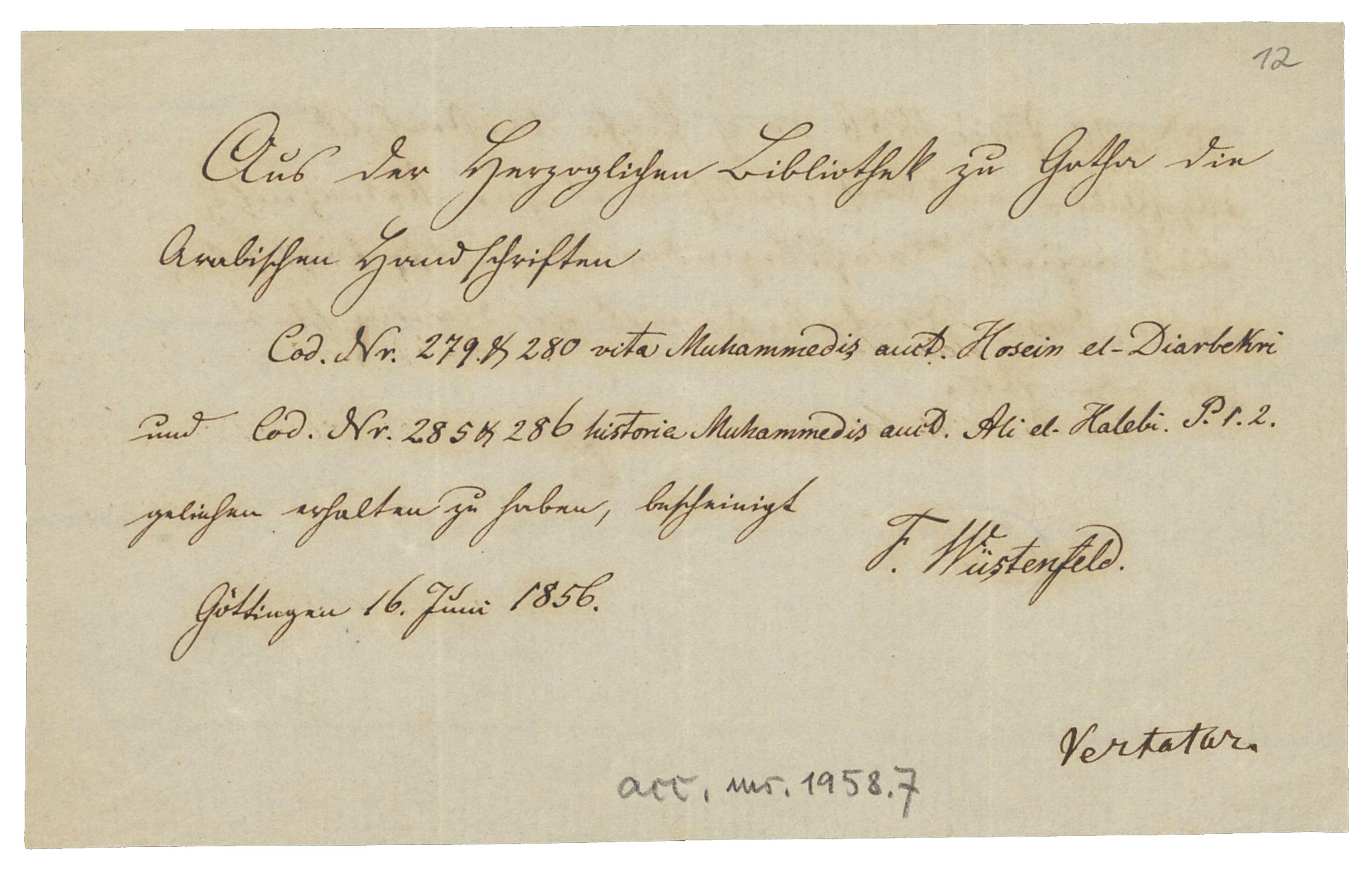

In his memoirs, Wüstenfeld vividly describes his two-week stay in the Gotha Library during the late autumn of 1832, describing it as a “major turning point” (“Hauptwendepunkt”) in his life.8Wüstenfeld 1890–1939, pp. 116–121/pp. 47–49, here p. 49. Thanks to the assistance of his brother-in-law’s brother, the Saxe-Coburg and Gotha court administrator David Friedrich, he was effortlessly granted access to the library, where he „enthusiastically explored“ (“mit Genuß” “durchforschte”) the Arabic manuscripts.9Wüstenfeld 1890–1939, p. 119/p. 48. In the afternoons and evenings, he continued his studies and transcriptions in his room, later taking some manuscripts with him to Göttingen. In subsequent years, numerous Gotha manuscripts were sent to Göttingen upon his request, secured by receipts (fig. 2). The “abundance of remarkable works” (“Menge der schönen Werke”) and the “courteous manner” (“liebenswürdige Weise”) of the Gotha librarians in supplying him with the materials he sought, as he later reflected, strengthened his resolve to dedicate his life to “contributing to the scholarly world by publishing Arabic texts” (“sich durch die Herausgabe Arabischer Werke der gelehrten Welt nützlich zu machen”).10Wüstenfeld 1890–1939, p. 121/p. 49.

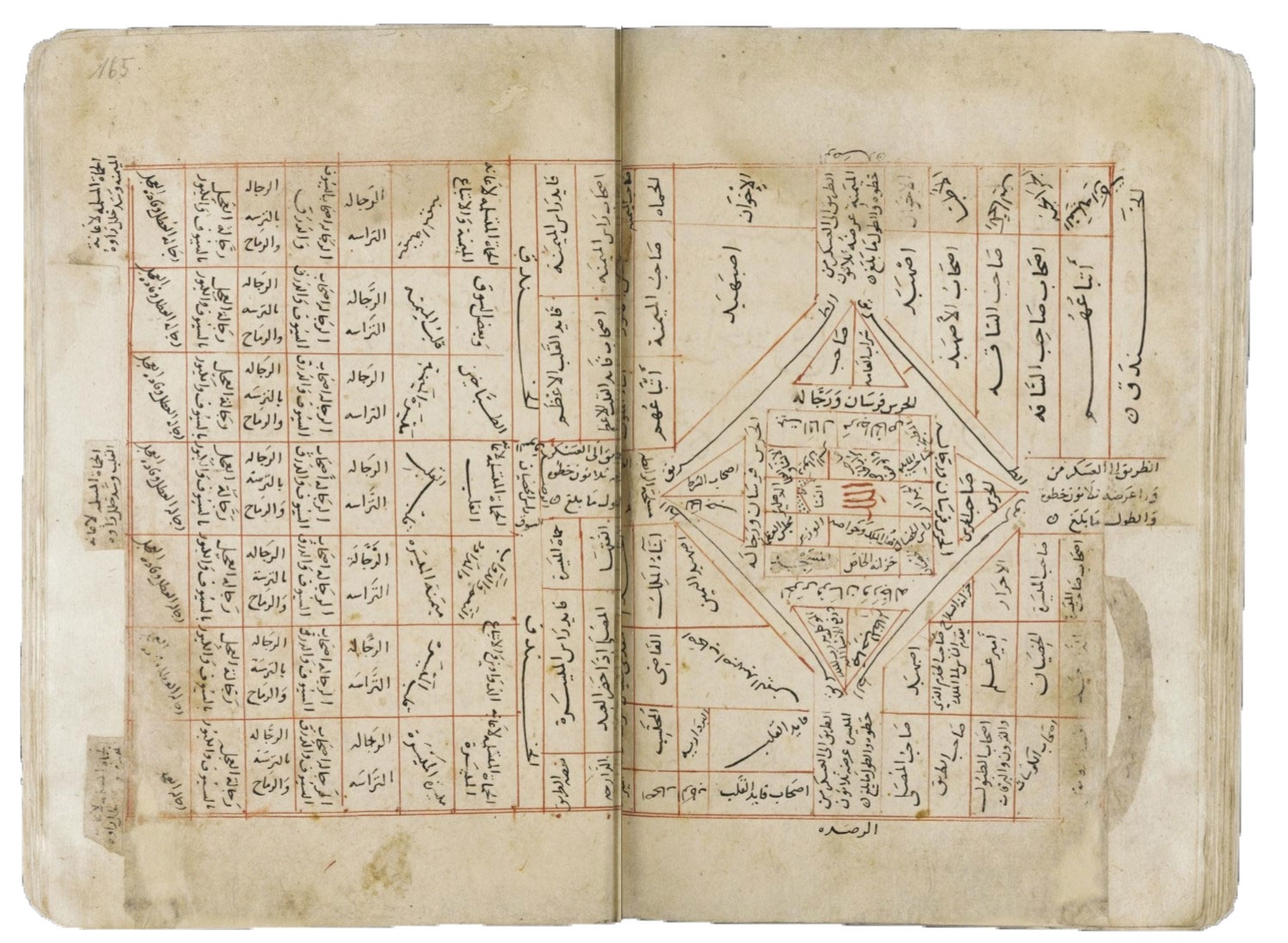

Among the numerous Gotha manuscripts that Wüstenfeld used for his editions is a historical military treatise on armies and warfare.11FB Gotha, Ms. orient. A 47, fol. 149r–215r. The Arabic text Nihāyat al-Suʾl by Muḥammad Ibn-ʿĪsā Ibn-Ismāʿīl al-Ḥanafī al-Aqsarāʾī, preserved in fragments, is part of an Arabic composite manuscript. It includes a previously unknown Arabic translation of Tactics on the basics of warfare written by the Greek author Aelian under Emperor Trajan at the beginning of the 2nd century AD.12George Fitzclarence, Earl of Munster had the work searched for in his catalogue of Arabic works on military affairs in the Orient (Wüstenfeld 1880, p. V). See also, among others, Lutful-Huq 1955; Schellenberg 2005. The work features diagrams illustrating various battle formations and troop arrangements, as depicted here (fig. 3).13FB Gotha, Ms. orient. A 47, fol. 164v–165r.

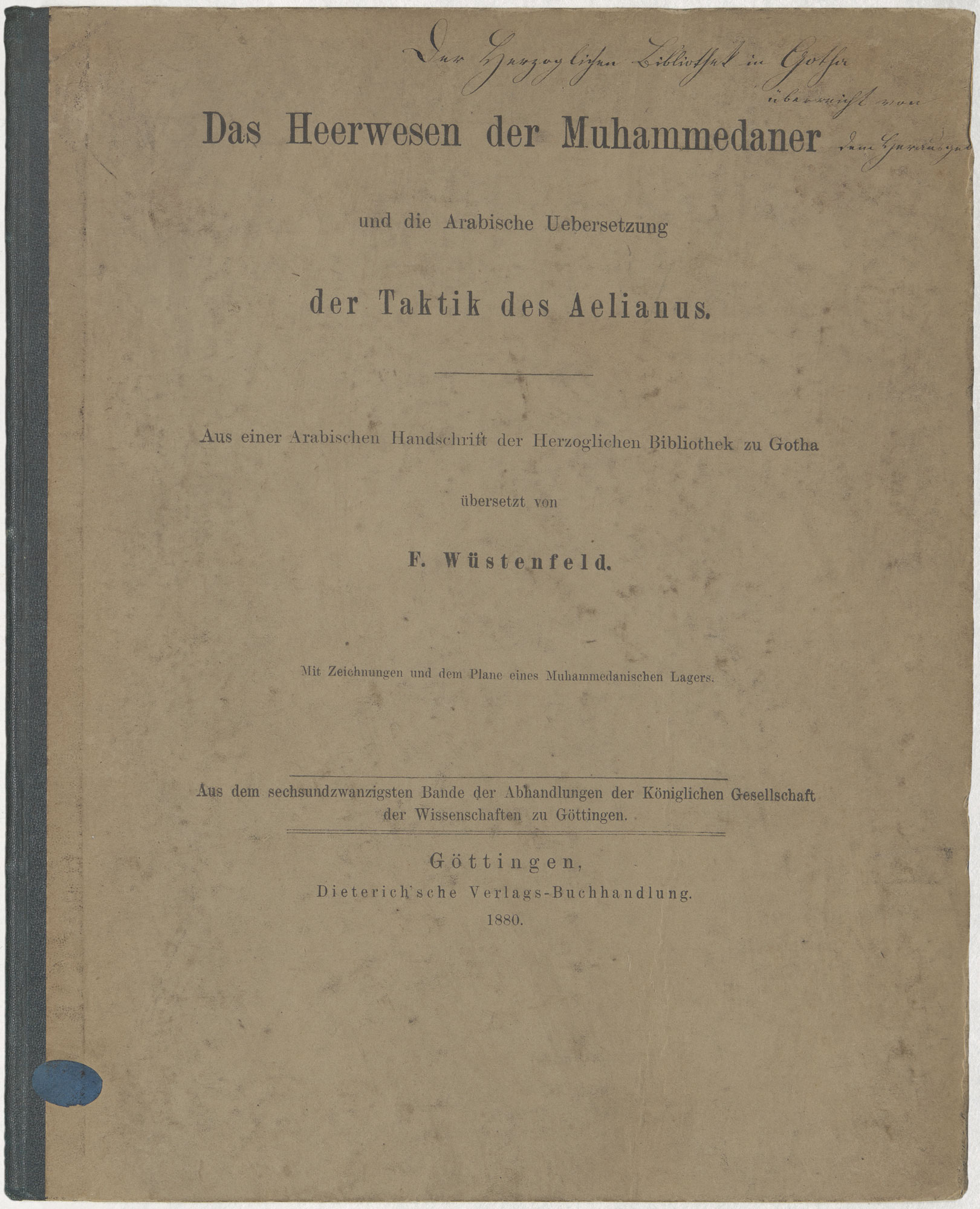

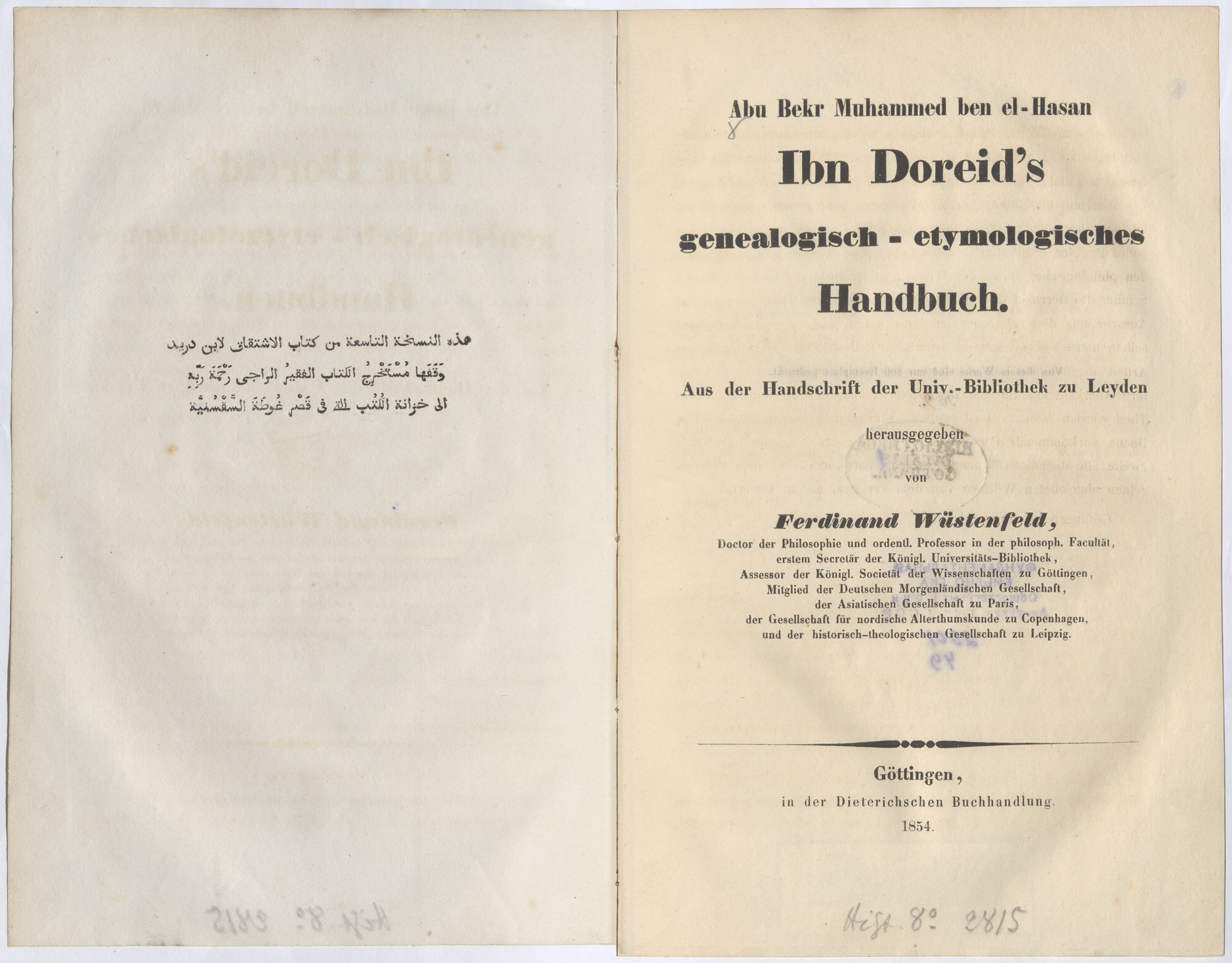

As in other cases, Wüstenfeld expressed his gratitude to the Ducal Library by sending copies of his edited works. The title page of the Heerwesen der Muhammedaner (The Military System of the Muhammadans) is now adorned with the handwritten note “Presented to the Ducal Library in Gotha by the publisher” (“An die Herzogliche Bibliothek in Gotha vom Verleger überreicht”, fig. 4, see also fig. 5). Furthermore, he included printed dedications to the library in several editions, such as Ibn Doreid’s genealogisch-etymologisches Handbuch (Ibn Doreid’s genealogical-etymological handbook), which Wüstenfeld published in 1854 (fig. 6).

Fig. 6: Printed dedication text for the Gotha Ducal Library in the edition of Ibn Doreid’s genealogisch-etymologischem Handbuch (Ibn Doreid’s Genealogical-etymological Handbook)

Ferdinand Wüstenfeld’s work represented a pivotal milestone in making Arabic literature accessible to European scholars. Through his meticulous editions and translations, he profoundly influenced the development of oriental studies in the 19th century and beyond, despite the fact that his methods were already subject to critical scrutiny during his lifetime.14Stein 1997, pp. 103ff.; Hartmann 1899, pp. 127f. The extensive correspondence between Wüstenfeld and various librarians, alongside his own reflective writings, highlights the crucial role that strong networks with fellow scholars and institutions – such as the Gotha Ducal Library – played in supporting and advancing his scholarly pursuits.

Hendrikje Carius

Dr. Hendrikje Carius is a historian, Head of User Services and the Digital Library Department and Deputy Director of the Gotha Research Library.

Primary Sources

- [Muḥammad Ibn-ʿĪsā Ibn-Ismāʿīl al-Ḥanafī al-Aqsarāʾī] [Eine Abhandlung über Kriegskunst = A treatise on the art of war], manuscript on paper, extract, undated. FB Gotha, Ms. orient. A 47, fol. 164v–165r.

- Martin Hartmann: Ferdinand Wüstenfeld, in: Orientalische Literaturzeitung 2/4 (1899), pp. 127–128.

- Abū Muḥammad ʿAbd al-Malik Ibn Isḥāq: Das Leben Muhammeds/Kitāb Sīrat Rasūl Allāh, ed. by Ferdinand Wüstenfeld. Göttingen 1858/59.

- Ferdinand, Wüstenfeld: Erinnerungen aus meinem Leben 1808−1836. Göttingen 1890–1939. Niedersächsische Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Göttingen, Cod. Ms. 2022.19. http://resolver.sub.uni-goettingen.de/purl?DE-611-HS-4017378 (accessed: 02.12.2024).

- Das Heerwesen der Muhammedaner und die Arabische Uebersetzung der Taktik des Aelianus. Aus einer Arabischen Handschrift der Herzoglichen Bibliothek zu Gotha, übersetzt von F. Wüstenfeld. Göttingen 1880. FB Gotha, Math 4° 00586/12, copy of the SUB Göttingen. http://dx.doi.org/10.25673/99715 (accessed: 02.12.2024).

Secondary Sources

- Karl Brethauer: Der Orientalist Professor Dr. Ferdinand Wüstenfeld erlebt die „Göttinger Revolution“ (6. bis 17. Januar 1831), in: Göttinger Jahrbuch 22 (1974), pp. 159–166.

- Gustave Dugat: Histoire des orientalistes de l’Europe du XIIe au XIXe siècle, vol. 2. Paris 1870.

- Johann Fück: Die arabischen Studien in Europa bis in den Anfang des 20. Jahrhunderts. Leipzig 1955. http://dx.doi.org/10.25673/33026 (accessed: 02.12.2024).

- Hilal Görgün: Wüstenfeld, Heinrich Ferdinand, in: Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı İslâm Ansiklopedisi 43 (2013), pp. 166–168. https://islamansiklopedisi.org.tr/wustenfeld-heinrich-ferdinand (accessed: 02.12.2024).

- Abul Lais Syed Muhammad Lutful-Huq: A critical edition of Nihāyat al-sūl wa’l-umnīyah fī taʿlīm aʿmāl al-furūsīyah of Muḥammad b. ʿIsā b. Ismāʿīl al-Ḥanafī. London 1955.

- Sabine Mangold: Eine “weltbürgerliche Wissenschaft” – Die deutsche Orientalistik im 19. Jahrhundert. Stuttgart 2004.

- Hans Michael Schellenberg: A Short Bibliographical Note on the Arabic Translation of Aelian’s Tactica Theoria, in: Philip Rance; Nicholas V. Sekunda (ed.): Greek Taktika: Ancient Military Writing and its Heritage Proceedings of the International Conference on Greek Taktika held at the University of Toruń, 7–11 April 2005. Gdańsk 2017, pp. 135–140.

- Peter Stein: Gotha und die Edition arabischer Quellentexte, in: Hans Stein (ed.): Orientalische Buchkunst in Gotha: Ausstellung zum 350jährigen Jubiläum der Forschungs- und Landesbibliothek Gotha. Gotha 1997, pp. 229–235.

- Julius Wellhausen: Wüstenfeld, Ferdinand, in: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie 55 (1910), pp. 139f. https://www.deutsche-biographie.de/pnd100836526.html#adbcontent (accessed: 02.12.2024).

Images

- Portrait of Ferdinand Wüstenfeld, in: Ibid.: Geschichte der Türken mit besonderer Berücksichtigung des vermeintlichen Anrechts derselben auf den Besitz von Griechenland. Leipzig 1899.

- Receipt for the loan of Arabic manuscripts, letter from Ferdinand Wüstenfeld to the Gotha Ducal Library, 25 September 1849–16 June 1856. Berlin State Library, Slg. Autogr.: Wüstenfeld, Ferdinand, fol. 10−12.

- Battle lines and troop formations in the Tactics edited by Wüstenfeld, in: [Muḥammad Ibn-ʿĪsā Ibn-Ismāʿīl al-Ḥanafī al-Aqsarāʾī]: [A treatise on the art of war], undated. FB Gotha, Ms. orient. A 47, fol. 164v–165r.

- Handwritten dedication by Ferdinand Wüstenfeld to the Gotha Ducal Library, in: Das Heerwesen der Muhammedaner und die Arabische Uebersetzung der Taktik des Aelianus: Aus einer Arabischen Handschrift der Herzoglichen Bibliothek zu Gotha, translated by F. Wüstenfeld. Göttingen 1880. FB Gotha, Math 4° 00586/12.

- Handwritten dedication by Ferdinand Wüstenfeld to the Gotha Ducal Library, in: Die Gelehrten-Familie Muhibbi in Damascus und ihre Zeitgenossen im XI. (XVII.) Jahrhundert. Göttingen 1884. FB Gotha, Biogr. 4° 306/6.

- Dedication text for the Gotha Ducal Library Gotha, in: Abu Bekr Muhammed ben el-Hasan: Ibn Doreid’s genealogisch-etymologisches Handbuch, ed. by Ferdinand Wüstenfeld. Göttingen 1854. FB Gotha, Gen. 8° 359/3.