“An ingenious and learned man”: Carolus Rali Dadichi’s journey from Aleppo to Gotha

On 25 July 1718, Gottfried Vockerodt (1665–1727), rector of Gotha’s Gymnasium illustre, welcomed an unusual guest. The man in his mid-twenties, with black hair and a dark complexion, had turned up claiming to be a Greek Orthodox Christian from Aleppo, in Syria, then an eastern province of the vast Ottoman Empire. He went by the name of Carolus Rali Dadichi.

He had arrived in Gotha preceded by testimonies of his extraordinary linguistic skills. He was blessed with an unusual capacity in Arabic, Syriac, Hebrew, Greek, Latin, Italian, French, and “other sciences” (“anderen Wißenschafften”). He combined a penetrating judgement with a phenomenal memory, such that he could recite by heart whole pages of Greek and Latin poetry. In short, as the professor at the Reformed University of Marburg, Johann Caspar Santoroc (1682–1745) told August Hermann Francke (1663–1727) at Halle, he was “an ingenious and learned man” (“ein geschickter und gelehrter Mensch”).

Santoroc recommended Dadichi for employment with Francke. He could perhaps assist the professor and figurehead of Halle Pietism with the edition of the Hebrew Bible that he then had in hand. Francke gladly encouraged Dadichi to come and join him on the Saale. But he directed him first to Gotha, where he was to lodge with Vockerodt, and to acquaint himself with one of Francke’s most promising theology students, Johann Heinrich Callenberg (1694–1760), who would accompany him to Halle for the beginning of the new university term.

Who was this “ingenious” and “learned” Syrian?

Two hundred years later, the librarian Wolfram Suchier (1883–1964) thought he had solved the mystery. In his 1919 book, C. R. Dadichi oder wie sich deutsche Orientalisten von einem Schwindler düpieren ließen, Suchier made the case that Dadichi was not a Syrian at all. Rather, he was “a swindler” and “a wicked imposter” (“ein abgefeimter Betrüger”) who tricked Vockerodt, Santoroc, Francke, and several other German scholars into believing a confected story about his Middle-Eastern origins. In fact, Suchier claimed, the man who had come to Germany claiming to be an Arabic-speaking Christian from Aleppo was nothing other than a talented but duplicitous Frenchman. “Carolus Dadichi” was the thinly veiled disguise of a man from Marseille called “Charles d’Atichy”.

About almost all of this, Suchier was wrong. But he was correct to sense that at least parts of Dadichi’s story did not quite add up. Dadichi never hid from the men he met in Germany the fact that he had first come to Europe to study in Paris with the Jesuits. He had spent time in Rome, where he had moved in the circles of cardinals, and even of the pope, Clement XI (1649–1721). He had then converted to the Reformed church at Geneva, and had ventured to several Reformed and Lutheran cities and universities, teaching Arabic, and dazzling the men he met with his prodigious learning and his formidable talents as a linguist.

But Dadichi’s presentation of himself as a “Greek” Christian obscured the true history of his childhood in Aleppo. He had, in fact, been christened and brought up as a Maronite. The Maronites were, in all essentials, Catholics. Dadichi’s imaginative curating of his back story therefore seems to have been an attempt to reinvent himself as a kind of “Protestant” Eastern Christian at the moment that he embarked on his career in Protestant Europe.

At any rate, in Gotha Dadichi was immediately set to work. Callenberg had apparently taken on some pupils during his summer vacation. Dadichi began teaching them the correct pronunciation of the Arabic letters. By the end of August, “several schoolboys” (“einige Schüler”) were attending Dadichi three days a week to learn Arabic. For his pains, Vockerodt paid him three thalers.

Dadichi also helped Callenberg with his own studies of Arabic. Callenberg had benefitted from the instruction of another Syrian Christian, Solomon Negri (1665–1729), who had visited Halle in 1715/16. With Dadichi, he set about deepening his knowledge. By the time Dadichi arrived in Gotha, students of Arabic, such as Callenberg, were well served by the fruits of more than a century of European Oriental scholarship. There were numerous grammars. There was a remarkably good dictionary, in the form of the Dutch scholar Jacobus Golius’s (1596–1667) Lexicon arabico-latinum (1653). And there were printed versions of the Old and New Testaments in Arabic translation, several Arabic-language histories, and – most significantly of all – the Qur’an, with a good Latin translation and a commentary, drawn from canonical Muslim exegetes. With Dadichi, however, Callenberg was able to practise the one thing he was unable to learn from books: the ability to speak Arabic, hearing the subtleties of pronunciation and colloquial forms of expression directly from a native speaker.

The two men also explored together whatever they could find in Gotha by way of artefacts from the Muslim world. By the eighteenth century, many of the great European libraries had amassed substantial collections of Arabic manuscripts. Gotha could hardly compete with Leiden, Oxford, Paris, or Rome. It was only in the nineteenth century, through the efforts of Ulrich Jasper Seetzen (1767–1811), that the library acquired the major part of its present Middle-Eastern collection. Nonetheless, Callenberg and Dadichi discovered some fascinating material in the ducal library.

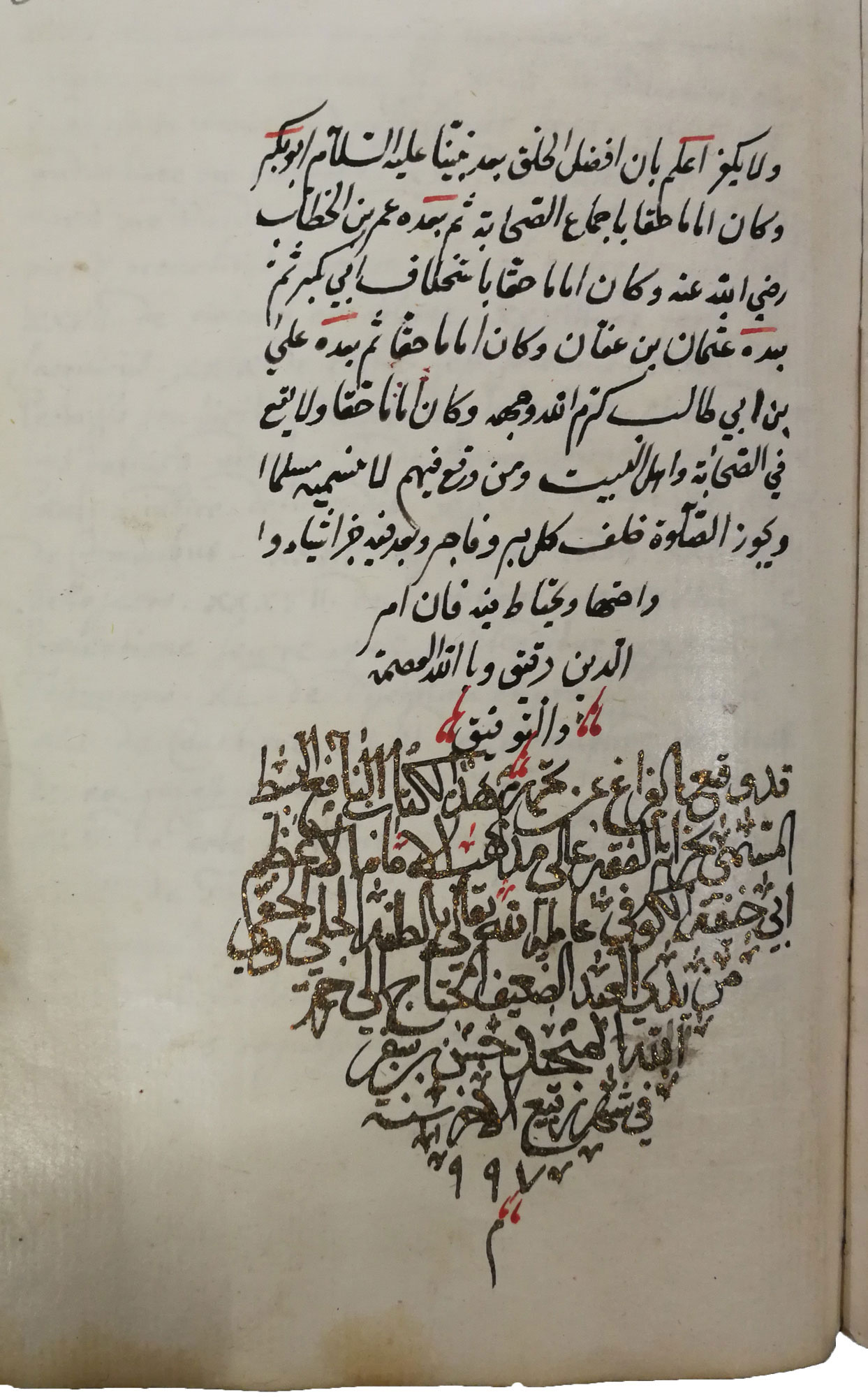

One item was a work entitled Khizānat al-fiqh (“Treasury of Law”), a compendium of Islamic legal theory, by the Ḥanafī judge and theologian, Abū al-Layth al-Samarqandī (d. 983). This manuscript, copied in the late sixteenth century, had once belonged to the Jena Orientalist, Johann Ernst Gerhard (1621–1668) (it is now FB Gotha, Ms. orient. A 991). Callenberg and Dadichi worked through the Arabic text word-by-word, with Dadichi pausing to explain any unfamiliar vocabulary. Callenberg also began a Latin translation. This early immersion in fiqh, or Islamic jurisprudence, proved formative for Callenberg’s later career. He became particularly interested in Islamic law governing relations with Christians. Indeed, Callenberg wrote his university dissertation on this topic, citing excerpts from the manuscript of Abū al-Layth al-Samarqandī’s compendium.

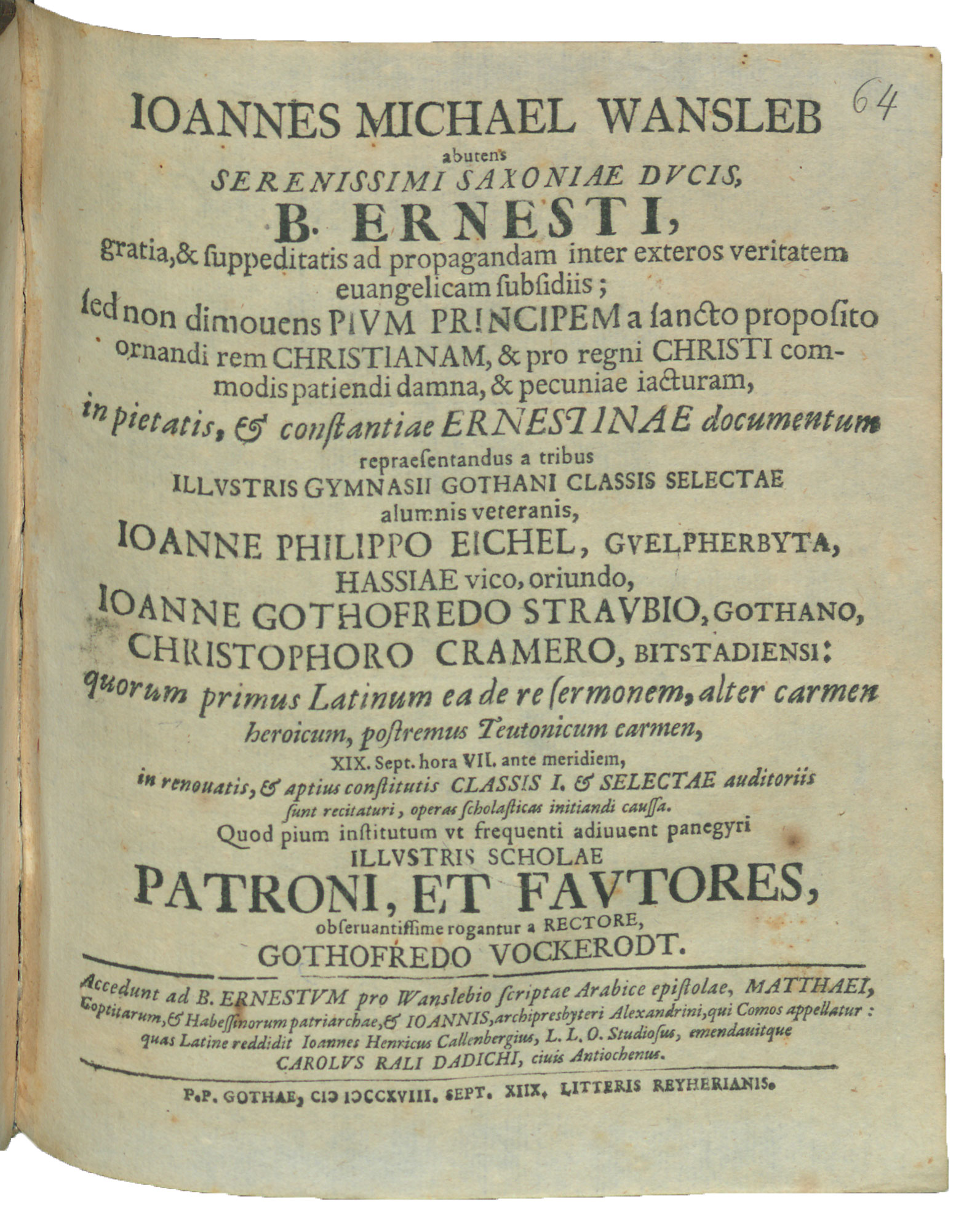

Another find had been produced, not by Muslims but by Christians. Two Arabic letters – one of them written on a sheet of paper more than two metres long – had come to Gotha thanks to an earlier episode in the history of German Orientalism. In the 1660s, the duke, Ernest I “the Pious” (1601–1675), and the man widely credited as the founder of Western Ethiopic studies, Hiob Ludolf (1624–1704), conceived a plan to send a Lutheran mission to Ethiopia. Johann Michael Wansleben (1635–1679) was dispatched to North Africa at the duke’s expense. He never made it farther south, however, than Upper Egypt. Things went from bad to worse when Wansleben – who had gone from Alexandria to Rome – converted to Catholicism. He later returned to the Ottoman Empire in the service of Louis XIV of France (1638–1715). Ernst and Ludolf never forgave what they always considered an act of gross betrayal.

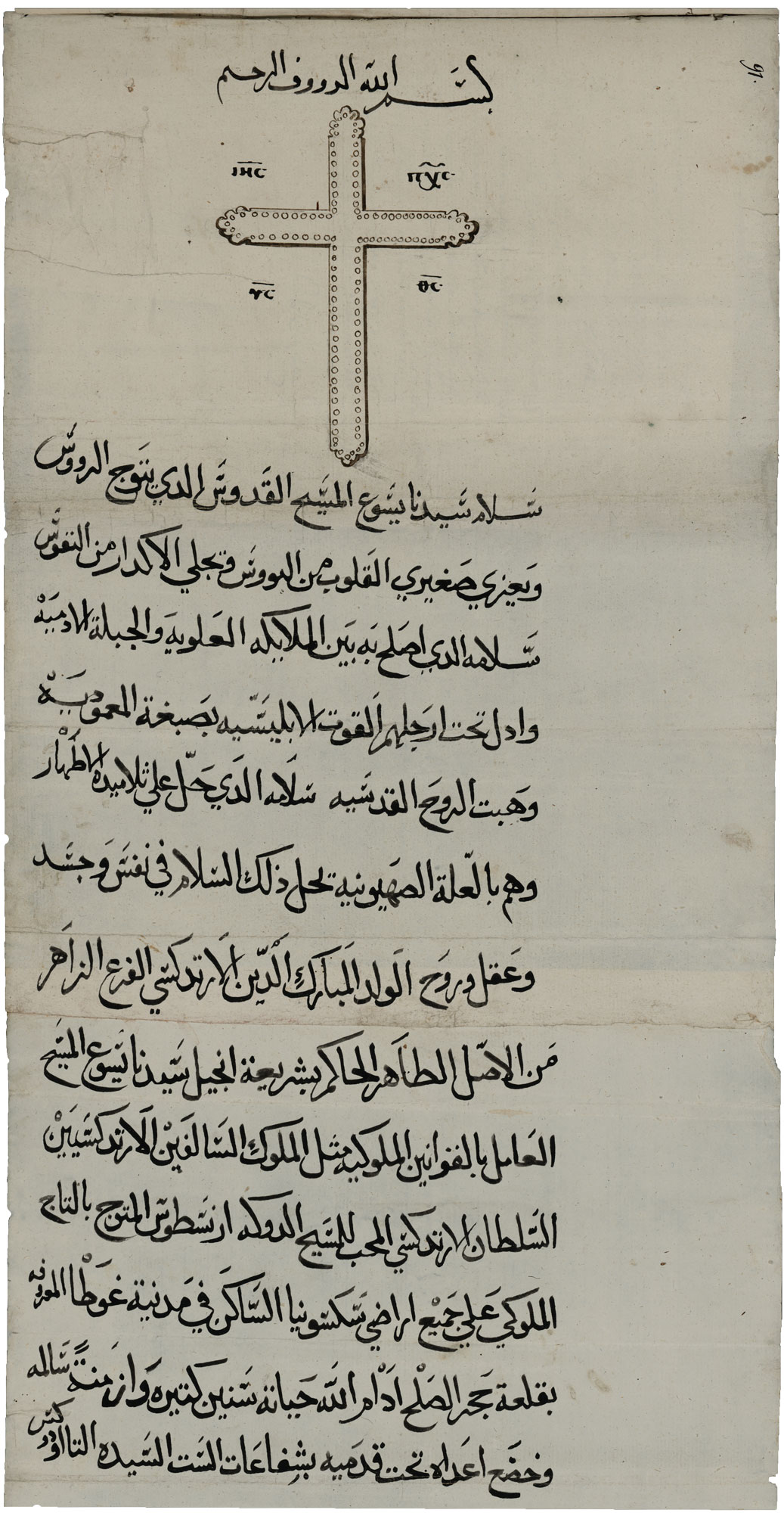

Fig. 2 John (Yūḥannā), archpriest (qummuṣ) of St. Mark’s Church: Letter to duke Ernst I. of Saxe-Gotha, Alexandria, 1665.

Wansleben forwarded the two letters (now FB Gotha, Chart. A 101, fols. 90 and 91) to Gotha, presumably in an attempt to account for his failure to reach Ethiopia. They were written by Matthew IV, the Coptic patriarch of Alexandria (d. 1675) and John, archpriest (qummuṣ) of St. Mark’s Church. Both letters – following elaborate salutations to the duke – warned of the many dangers of travelling to Ethiopia. The route was difficult. It would be necessary to pay tributes along the way. Most troublingly of all, the Ethiopians would kill any Europeans who arrived, because of the discord stirred up by Jesuit missionaries.

In September 1718, Callenberg contributed a Latin translation of both letters to a short memorial to Ernst the Pious printed at Gotha. Dadichi was credited on the title page with “correcting” the text. Callenberg’s handwritten draft reveals how Dadichi improved the final version. For instance, John wrote that Wansleben came to him in the thaghr of Alexandria. Callenberg initially rendered this word as “portus” (“port”). Dadichi amended it to the more correct “fines” (“boundaries”). Likewise, reporting the patriarch’s warning to Wansleben, John referred to the fitna that had arisen between the Ethiopians and the Europeans. Callenberg’s draft has “rebellio” (“rebellion”). Dadichi amended the word to “rixa” (“quarrel”).

In his preface to the printed letters, Callenberg was full of praise for his “very learned” (“eruditissimus”) and “very skilled” (“doctissimus”) collaborator. But his and Vockerodt’s letters to Francke hint that accommodating their Syrian guest was not all plain sailing. Dadichi was apparently too proud to accept the three thalers that Vockerodt paid him for teaching Arabic. Vockerodt was therefore forced to send him the money in a sealed, anonymous package. Both Vockerodt and Callenberg also had some scruples about Dadichi’s morals and religious conduct, prompted in part by their suspicions of a young man who had spent seven years under the Jesuits.

By 11 September, Dadichi had arrived in Halle. There, he spent a year teaching Arabic, Syriac, and Persian. He then moved on to Leipzig, Berlin, and – via Italy, Spain, France, and the Netherlands – to London, where he died in April 1734, aged just forty.

His two-month stay in Gotha was, then, merely a brief interlude in his European odyssey. But it was not without consequences – not least, setting Johann Heinrich Callenberg on his career as an Arabist through both men’s exploration of the library’s Arabic manuscripts. Carolus Rali Dadichi was surely one of the most colourful characters to pass through Gotha during its early modern history. We can only guess at what the German schoolboys thought about their Arabic lessons with their learned and unusual teacher from Aleppo.

Simon Mills

Dr. Simon Mills is Senior Lecturer in Early Modern History, Newcastle University.

Sources

- Callenberg to Francke, 02.08.1718, SBB, Nachlass A. H. Francke, 8/3: 9

- Francke to Dadichi, 14.06.1718, SBB, Nachlass A. H. Francke, 1a/1A: 23

- Santoroc to Francke, 22.05.1718, AFSt/H A 171: 171

- Santoroc to Francke, 19.02.1719, AFSt/H C 659: 1

- Vockerodt to Francke, 25.08.1718, SBB, Nachlass A. H. Francke, Slg. Autogr: Vockerodt, Gottfried

- Vockerodt to Francke, 14.08.1718, SBB, Nachlass A. H. Francke, 22/5: 72

- AFSt/H K 88, ff. 54–105 and 169–173 (Callenberg’s translations of Khizānat al-fiqh); ff. 44–52 and 106–168 (notes on vocabulary from Khizānat al-fiqh)

- AFSt/H K 88, ff. 19–30 (Callenberg’s draft translations of the Arabic letters from Egypt)

- Johann Heinrich Callenberg: Iuris circa Christianos muhammedici particulae e codicibus Moslemorum eruit et die Aug. publicae disquisitioni exposuit Io. Henric. Callenberg… respondentis munus obeunte Ludov. Christ. Vockerodt. Halle [1729].

- Gottfried Vockerodt: Ioannes Michael Wansleb abutens Serenissimi Saxoniae Ducis, B. Ernesti, gratia… documentum… Accedunt ad B. Ernestum pro Wanslebio scriptae arabice epistolae, Matthaei, Coptitarum, & Habessinorum patriarchae, & Ioannis, archipresbyteri Alexandrini, qui Comos appellatur: quas latine reddidit Ioannes Henricus Callenbergius… emendavitque Carolus Rali Dadichi, civis Antiochenus. Gotha 1718.

Literature

- Alastair Hamilton (ed.): Johann Michael Wansleben’s Travels in the Levant, 1671–1674. An Annotated Edition of His Italian Report. Leiden 2018.

- Wolfgang Hage: Carolus Dadichi in Marburg (1718). Bittgesuch eines rum-orthodoxen Studenten im Universitäts-Archiv, in: Oriens Christianus 95 (2011), pp. 16–31.

- Simon Mills: Türkenbeute in Halle: The Spoils of War and the Study of Islam in an Eighteenth-Century Pietist Orphanage, in: Erudition and the Republic of Letters 9.3 (2024), pp. 363–389.

- Dmitry A. Morozov and Ekaterina Gerasimova: Carolus Rali Dadichi and the Bibliotheca orientalis by J. S. Assemani: A Letter of an Oriental Author on the Popularization of Syriac Literature in Europe, in: N. L. Muskhelishvili and N. N. Seleznyov (eds.), Simvol 61: Syriaca, Arabica, Iranica. Paris/Moscow 2012, pp. 357–370 [in Russian].

- C. F. Seybold: Der gelehrte Syrer Carolus Dadichi (†1734 in London), Nachfolger Salomo Negri’s (†1729), in: Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft 64.3 (1910), S. 591–601.

- Wolfram Suchier: C. R. Dadichi oder wie sich deutsche Orientalisten von einem Schwindler düpieren ließen. Ein Kapitel aus der deutschen Gelehrtenrepublik der ersten Hälfte des 18. Jahrhunderts. Halle 1919.

Images

- Ḫizānat al-fiqh (“Treasury of the Law”). FB Gotha, Ms. orient. A 991, f. 135r.

- John (Yūḥannā), archpriest (qummuṣ) of St. Mark’s Church: Letter to duke Ernst I. of Saxe-Gotha, Alexandria, 1665. FB Gotha, Chart. A 101, f. 91r.

- Ioannes Michael Wansleb abutens Serenissimi Saxoniae Ducis, B. Ernesti, gratia… Gotha 1718. FB Gotha, P 8° 08466 (64).