From Cairo to Gotha and the Vatican

The Trade of Cairo’s early Qur’ans

The Gotha Research Library holds an important collection of fragments from early Qur’an manuscripts on parchment that were once preserved in the Mosque of ʿAmr b. al-ʿĀṣ (d. 664), governor of Egypt between 640 and 664. The Mosque was built in Fusṭāṭ, the ancient urban foundation located south of modern-day Cairo. Soldiers of the Arab army settled there in 641–642 when they conquered Egypt. ʿAmr b. al-ʿĀṣ founded the mosque that today bears his name (see fig. 1).

In 1809, the German explorer Ulrich Jasper Seetzen (1767–1811) visited the mosque. He was shown a part of the mosque where the old unused manuscripts were kept in piles on the floor:

Seetzen later claimed that he did not manage to buy the precious exemplar that he saw. Nevertheless, he sent some important Qur’an leaves to the Ducal Library in Gotha.

The mosque of Fusṭāṭ was a repository of old and unused documents. Such repositories were established to preserve written artefacts, similar to genizahs in Jewish culture.2Vorderstrasse-Treptow 2015. The mosque and its collection of early Qur’ans received significant attention from travellers, scholars, and antiquarian dealers since the seventeenth century. This was the period when European scholars and collectors started to study manuscripts of the Qur’an and became interested in its ancient script, orthography, and content. The enormous collection of Qur’an manuscripts preserved in the Mosque of ʿAmr b. al-ʿĀṣ was dispersed piece by piece over four centuries. Parts of the manuscripts – leaves, quires, and nearly complete codices – are now scattered in institutions all over the world. The early Qur’ans of the Gotha collection were among the first artefacts which became available to scholars. They were studied and used for the understanding of the written transmission of the Qur’anic text from the nineteenth century on.

Qur’an manuscripts scattered all over the world: Matching Ms. orient. A 432 and other fragments

Scholars were able to link some of the Qur’an fragments from Fusṭāṭ preserved in Gotha to fragments in other collections. For example, some fragments have been linked with manuscripts in the Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF) in Paris. However, some scattered fragments that originated from the same historical artefacts have been identified only recently. Further links will likely be discovered in the future. This network of relationships between fragments is part of the fascinating history of the afterlife of manuscripts. Tracing such relationships allows for the virtual reconstruction of the historical artefact from which the fragments were taken. Such a study is part of the research carried out by the project “What is in a scribe’s mind and inkwell” conducted at the Cluster of Excellence “Understanding Written Artefacts” (UWA) at the Centre for the Study of Manuscript Cultures (CSMC) in Hamburg.

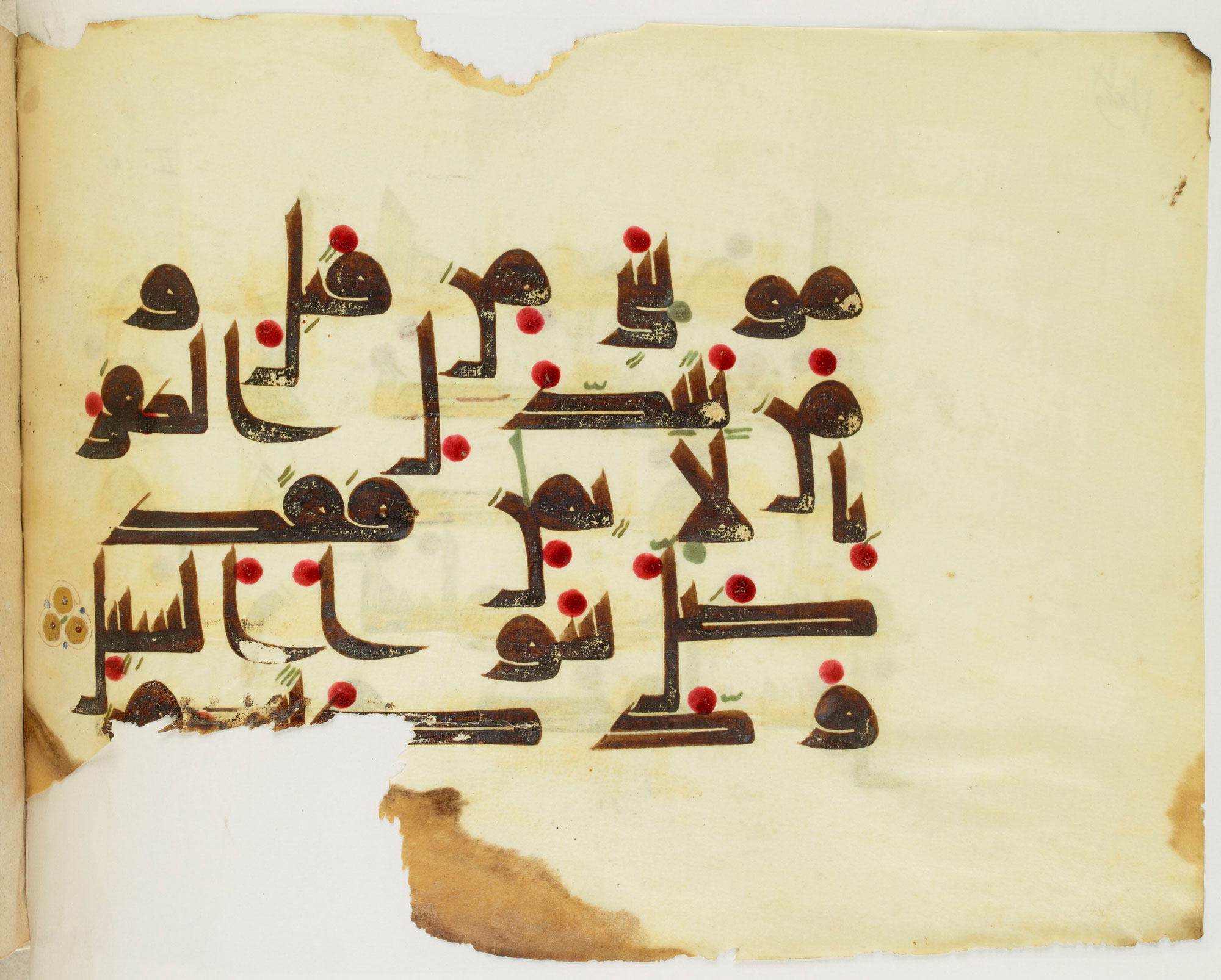

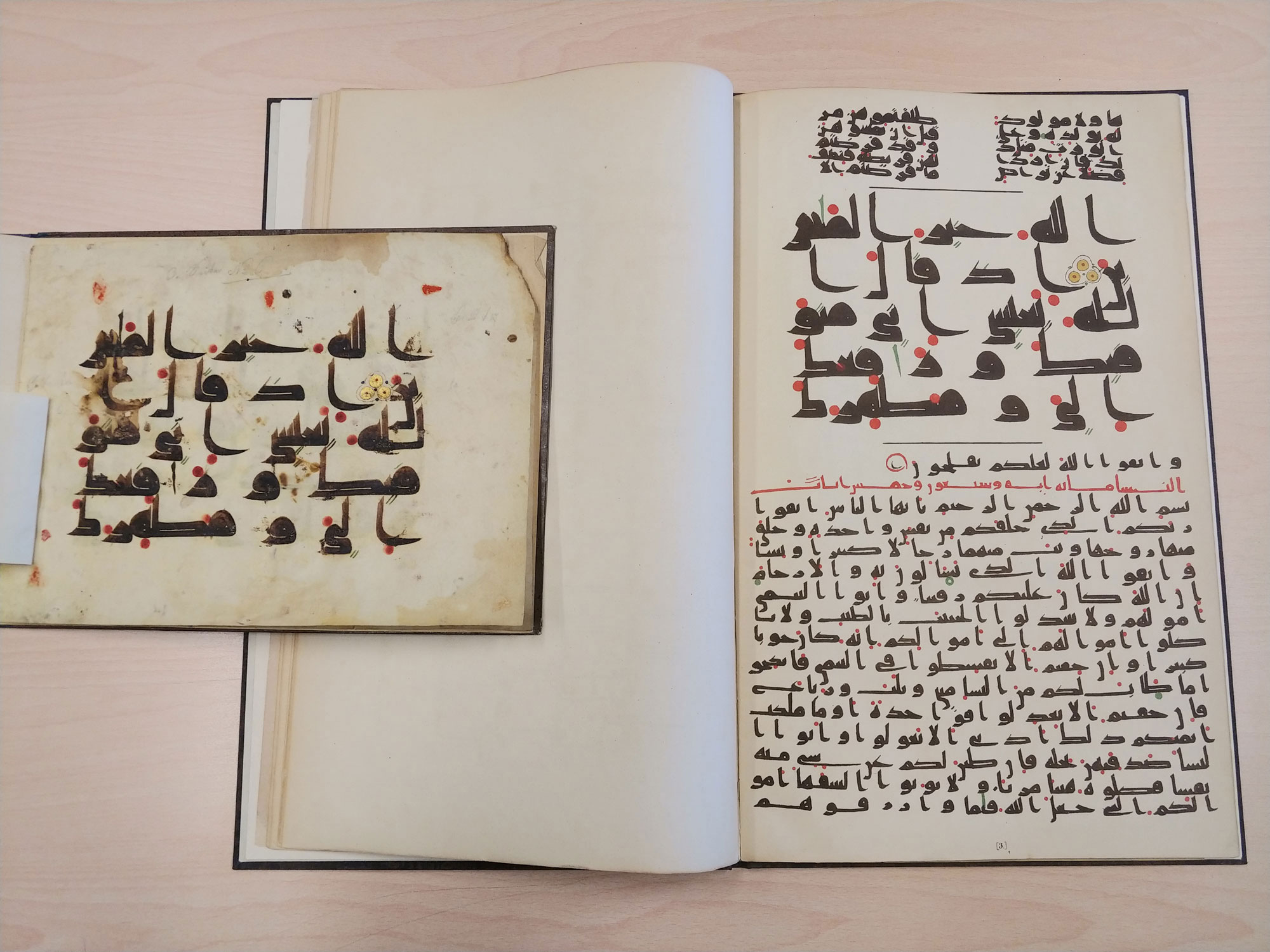

The link between the two parchment leaves of Ms. orient. A 432 preserved in Gotha and the seventy-two leaves of Ar. 341b (ff. 130–201) in Paris was recognized by François Déroche in 1983 (figs. 2 and 3).3Déroche 1983. The provenance of the Paris leaves is well known. They were part of a collection gathered by Jean-Louis Asselin de Cherville (1772–1822), which was sold by his heirs to the Bibliothèque nationale de France in 1830. Asselin de Cherville served as agent of the Consulat général of France and Italy in Cairo from 1806 to 1822. His position allowed him to collect Arabic manuscripts. His purchases included, according to him, “a considerable collection of Qur’anic leaves for palaeographic studies”.

The French orientalist William MacGuckin de Slane (1801–1878) was able to trace the link between the Paris leaves and another scattered leaf in Copenhagen.4De Slane 1883–1895, p. 98. The leaf is preserved in the Royal Library of Copenhagen (Det Kongelige Bibliotek, Cod. Arab. 42). Because of a handwritten note, it is known that the Copenhagen leaf was transferred to Europe long before Seetzen’s visit to the Fusṭāṭ mosque. An owner’s mark suggests that the early Qur’ans in the Royal Library of Copenhagen were acquired by Friedrich Buchwald (1605–1676) who brought them to Denmark. They were added to the Royal Library during the reign of King Christian VII (1766–1808).5Perho 2007, p. xix–xx, 105–106.The Copenhagen Qur’an leaves were extensively studied in the eighteenth century. They constituted the material corpus based on which the discipline of Arabic palaeography was founded.

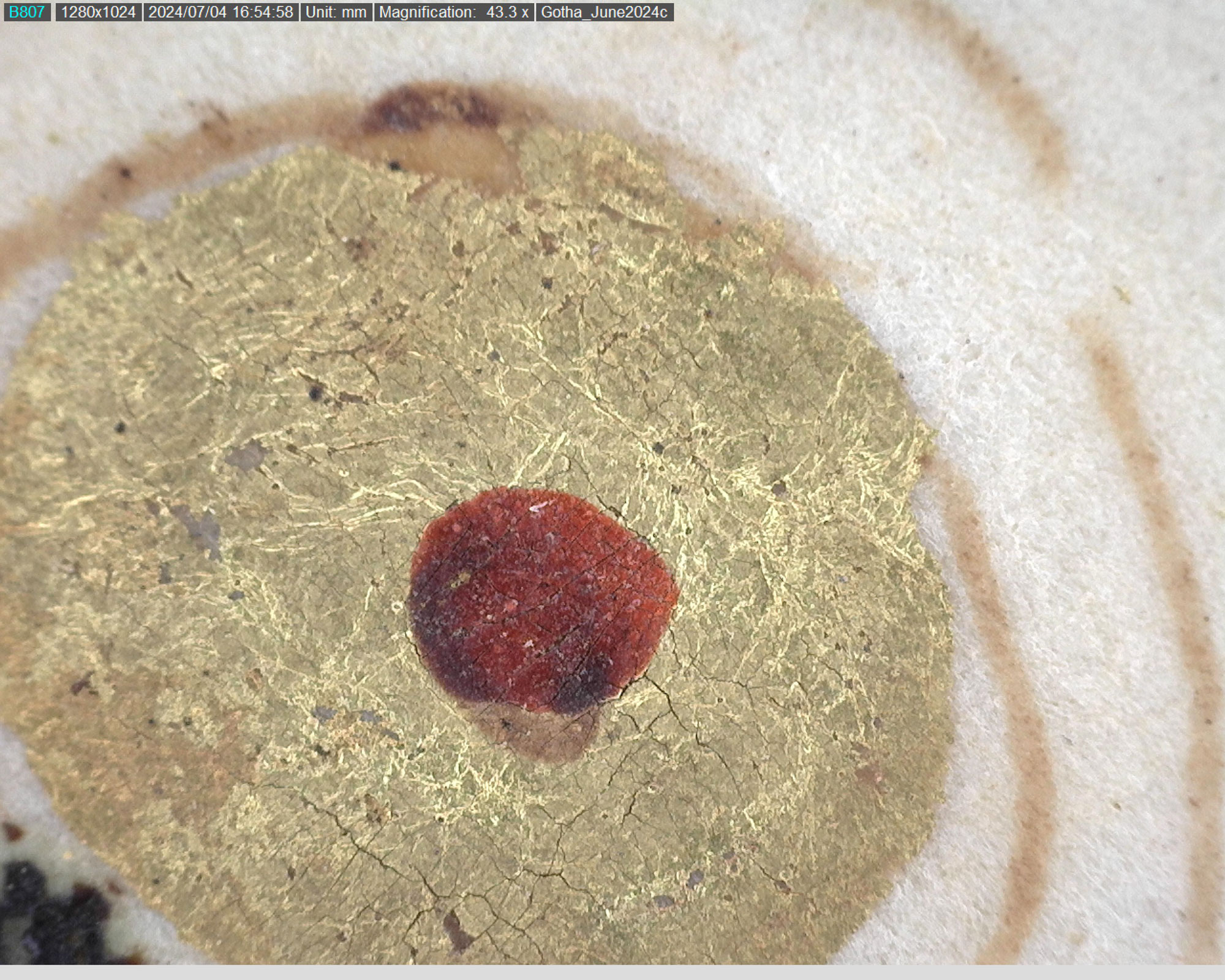

There are further pieces that can be traced back to the original artefact from Fusṭāṭ. A leaf from the Khalili collection (KFQ 35) has the same features: the size of the text area, the script style, the green strokes used as diacritics to distinguish homograph letters, and the markers used to signal verse endings. A symbol is inserted to mark a group of ten verses, and it refers to a larger and richly decorated medallion in the margin.6The leaf is described in Déroche 1992, p. 77.

Further scattered leaves are part of the collection assembled by one of the most successful Italian book dealers of the twentieth century, Tammaro De Marinis (1878–1969), the “prince of the bibliophiles”. In 1946, he donated one lot of very early Qur’an manuscripts to the Vatican Library. The lot includes some scattered fragments that once belonged to the same artefact from which the Gotha fragments derive. A few further leaves in the recently established collection of the Museum of Islamic Art (MIA) in Doha are likely connected to De Marinis and the Italian book trade. They can perhaps also be linked to the same Qur’an, but a definitive conclusion cannot be reached just yet since this is still work in progress.

From early modern explorers to book dealers of the twentieth and twenty-first century

Over the centuries, many different individuals and institutions collected early Qur’ans: travellers and explorers, scholars, manuscript collectors, antiquarian dealers, and acquisitions departments of modern museums and collections. In the case considered here, one can observe which leaves and how many of them were removed from the original artefact if one develops a hypothetical chronological order of the acquisitions.

The total number of leaves of the original artefact – if complete – amounted to around 3.500 leaves. Buchwald and Seetzen took three leaves from the first two surahs of the Qur’an in 1626 and 1809. By 1814, Asselin de Cherville had assembled 72 leaves, which were removed from various parts of the Qur’an, specifically from surahs 2 to 64. The acquisitions by De Marinis, Khalili and the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha were made by collectors, antiquarian dealers, and private owners; they were no longer the direct acquisitions of travellers and explorers. De Marinis acquired nine leaves with discontinuous fragments from surahs 2 to 43 and Khalili purchased one leaf with a part of surah 53. The identification of the fragments acquired by the Museum of Islamic Art is still a work in progress, as mentioned above, but they likely consist of a few leaves.

One leaf traced in the Doha collection was acquired together with other manuscripts. They were kept in folders used by the previous owner to indicate the content. The notes written on the folders are in Latin and Italian. This precious private Italian collection includes some of the masterpieces among the early Qur’an manuscripts kept in the Fusṭāṭ mosque.7See Fedeli 2011 and Gonella (ed.) 2022 on the entire collection. The handwriting of the Italian notes on the folders suggests that the book dealer who collected these manuscripts was De Marinis, the man who also donated the Kufic parchment to the Vatican Library. The Italian network of book and manuscript dealers who came into possession of important Qur’an fragments at the beginning of the twentieth century is still an area to be investigated.

Accessing the manuscripts through images

The links between the leaves preserved in Gotha, Copenhagen, and Paris with those in the Biblioteca Vaticana, on the one hand, and the Khalili Collection and the MIA Collection in Doha, on the other hand, have not been identified in previous scholarship.

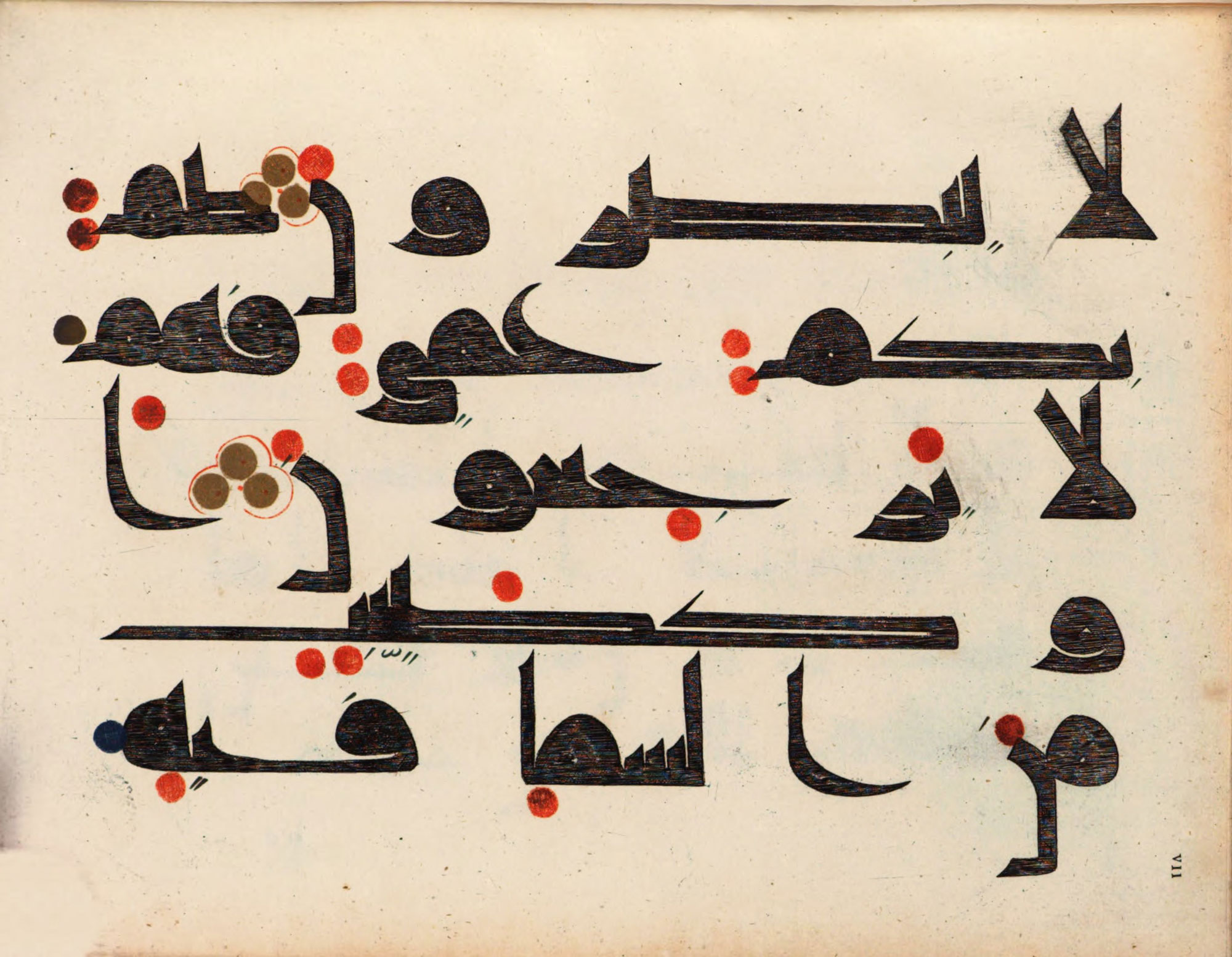

The Doha Museum acquired the manuscript fragments only recently, which explains why the connection has not yet emerged. The missing link to the fragments in the Biblioteca Vaticana is more surprising. One explanation is that the manuscripts were available as visual objects in the form of drawings, engraved printings, lithographs, printed images of different quality, and only recently digital images. Facsimiles of the Copenhagen and the Gotha manuscripts were published by Jacob Christian Lindberg (1797–1857) in 1830 in the form of engravings and by Johann Heinrich Möller (1792–1867) in 1844 in the form of lithography (figs. 4 and 5). Engraved drawings and lithographic reproductions of Qur’an leaves were regularly commissioned until the beginning of the nineteenth century. This allowed scholars who did not have the original manuscript at their disposal to study the text.

Pictures of the Vatican leaves were printed with a sepia effect by the Italian scholar of Arabic Giorgio Levi Della Vida (1886–1967). The Vatican Library undertook a large project of digitization of its holdings in the framework of the DigiVatLib initiative only recently. It is hard to perceive the characteristics of the Vatican leaves based on the sepia pictures from the 1940s, although their publication was an extraordinary achievement at the time. Ironically, the availability of such material early on meant that researchers focused their efforts for a long time on visual materials of a lesser quality than in the case of those produced today.

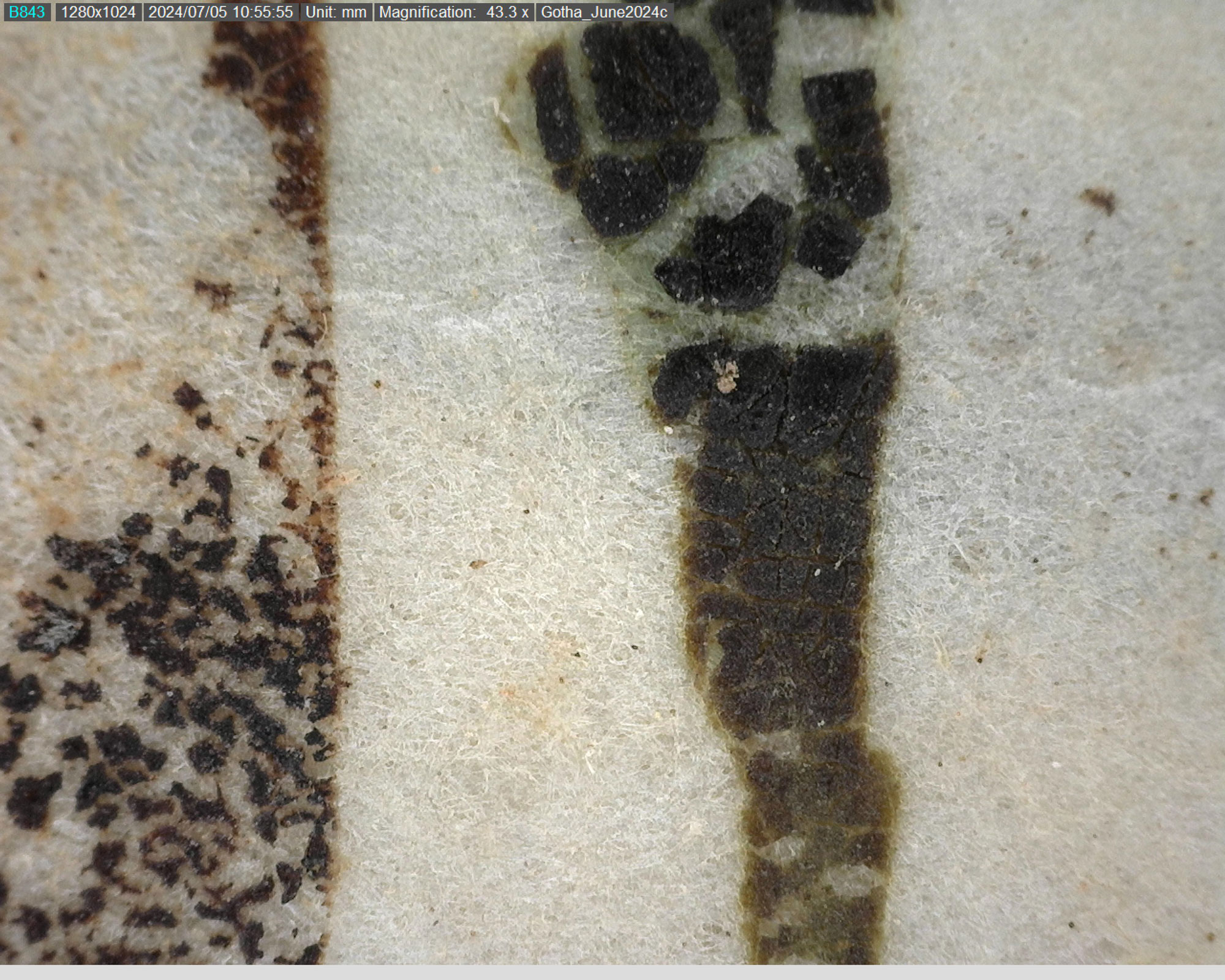

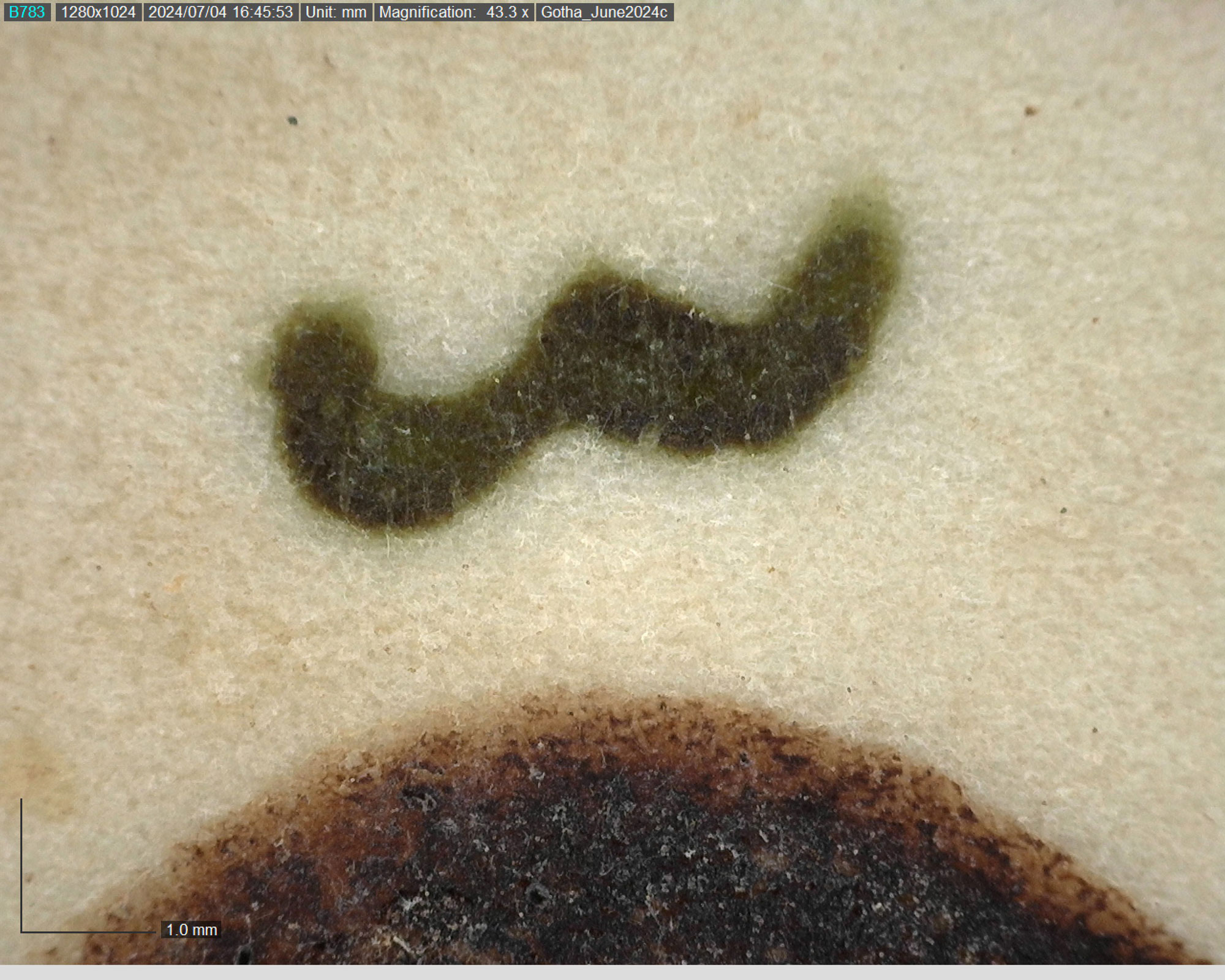

In the case of the early Qur’an manuscripts preserved in Gotha, the original objects have been easily accessible in the form of facsimiles and microfilms. Today, digital reproductions – primarily stored in the Digitale Historische Bibliothek Erfurt/Gotha8https://dhb.thulb.uni-jena.de/templates/master/template_dhb/index.xml. – allow scholars to access the manuscripts in greater detail. Modern technology enhances our understanding of the manuscripts and their production. A microscope, for example, can reveal elements invisible to the naked eye. The level of granularity of data observed and measured in each of the scattered fragments influences how scholars perceive of the connections between them. For example, the identification of the common elements in the subdivision markers (fig. 6) are essential for verifying the similarity of the Gotha and Vatican manuscripts.

An interdisciplinary approach using history, philology and science is the core of the methodology of the current project “What is in a scribe’s mind and inkwell”. With such an approach, it is not only possible to reconstruct the history of the collection of early Qur’an manuscripts preserved in Gotha in terms of provenance and to disentangle the stages of its history. It becomes possible to go further back in history and to study the material layers and history of an artefact in terms of the use of parchment and inks. Manuscripts are not fossilized objects created in a single step but rather living objects that are subject to interactions with their users, keepers, readers and with the socio-historical and geographic environment. Looking at the inks that were used by the scribe at the time when the primary layer was produced and during the following temporal layers can be of crucial importance for investigating the history of manuscripts.

A first analysis of the Qur’an manuscripts conducted in June 2024 in Gotha raised questions about the stratigraphy and the scribal agency connected with each layer. A microscope camera reveals this stratigraphy. The physical strata can suggest a chronological development of certain grammatical features. For example, if the same green ink of two distinct orthographic signs is used, this can allow for identifying the same scribal agency behind both phenomena (figs. 7 and 8). Such signs and the layers they suggest can shed light on the history of the grammar and recitation of the text.

Further analyses will be conducted in spring 2025 by a team of the laboratory of CSMC Hamburg from the Cluster of Excellence “Understanding Written Artefacts” to identify the elemental and chemical composition of details observed during the first phase of the project. Updates will be provided on the website of the project “What is in a scribe’s mind and inkwell”.

Alba Fedeli

Dr. Alba Fedeli is a researcher at the Cluster of Excellence “Understanding Written Artefacts” (UWA) at the Centre for the Study of Manuscript Cultures (CSMC), University of Hamburg.

Sources

- Gotha Research Library, University of Erfurt, Ms. orient. A 432.

- Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, Arabe 341b.

- Royal Library of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Cod. Arab. 42.

- Nasser D. Khalili collection of Islamic art, London, KFQ 35.

- Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vatican City, Vat.Ar.1605.

- Museum of Islamic Art, Doha, MS.63.2007.

Literature

- François Déroche: Les manuscrits du coran. Aux origines de la calligraphie coranique. Catalogue des manuscrits arabes. Deuxième partie: manuscrits musulmans, Vol. I–1. Paris 1983.

- François Déroche: The Abbasid Tradition. Qur’ans of the 8th to the 10th Centuries AD. London 1992.

- William MacGuckin Baron De Slane: Catalogue des manuscrits arabes. Paris 1883–1895.

- Alba Fedeli: The Provenance of the Manuscript Mingana Islamic Arabic 1572: Dispersed Folios from a few Qur’ānic Quires, in: Manuscripta Orientalia 17,1 (2011), pp. 45–56.

- Julia Gonnella et al. (eds.): Museum of Islamic Art: The Collection. London/Doha 2022.

- Giorgio Levi Della Vida: Frammenti coranici in carattere cufico nella Biblioteca Vaticana (codici vaticani arabi 1605 e 1606). Città del Vaticano 1947.

- Liv Ingeborg Lied: Digitization and Manuscripts as Visual Objects: Reflections from a Media Studies Perspective, in: David Hamidović, Claire Clivaz, and Sarah Bowen Savant (eds.): Ancient Manuscripts in Digital Culture. Visualisation, Data Mining, Communication. Leiden 2019, pp. 24–25.

- Ilenia Maschietto (ed.): “Multa renascentur”. Tammaro de Marinis studioso, bibliofilo, antiquario, collezionista. Venice 2023.

- Irmeli Perho: Catalogue of Arabic Manuscripts: Codices Arabici et Codices Arabici Additamenta. Vol. 1. Copenhagen 2007.

- Ulrich Jasper Seetzen: Reisen durch Syrien, Palästina, Phönicien, die Transjordan-Länder, Arabia Petraea und Unter-Aegypten, edited by Friedrich Kruse. Vol. 3. Berlin 1855.

- Tasha Vorderstrasse and Tanya Treptow (eds.): A Cosmopolitan City. Muslims, Christians and Jews in Old Cairo. Chicago 2015.

Images

- The Mosque of ʿAmr b. al-ʿĀṣ in Fusṭāṭ. Photograph taken in 1893. Brooklyn Museum Libraries. Image credit: Wikimedia, Mosque: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amr_ibn_al-As_Mosque#/media/File:%22Mosque_of_Amr_in_Cairo.%22_1893.jpg.

- Gotha Research Library, University of Erfurt, Ms. orient. A 432, f. 2v. A Qur’an fragment from Fusṭāṭ which includes verses 54 and 55 of surah 3.

- Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, Arabe 341b, f. 149v. A fragment of the same Qur’an from Fusṭāṭ as in fig. 2. This fragment includes verses 108 and 109 of surah 2.

- Gotha Research Library, University of Erfurt, Ms. orient. A 432, f.2v. Original manuscript (left side) and facsimile published by Johann Heinrich Möller (1792–1867) in 1844 (right side). © Alba Fedeli.

- Facsimile of another fragment of the same manuscript by Jacob Christian Lindberg (1797-1857), published in 1830. Copenhagen, Det Kongelige Bibliotek, Cod. Arab. 42, f.3r.

- A subdivision marker with concentric circles in gold, red and blue in Ms. orient. A 432. Photograph taken with a microscope. © Alba Fedeli.

- Orthographic detail from Ms. orient. A 432 (lengthening of vowel /a/ in green ink). Photograph taken with a microscope. © Alba Fedeli.

- Orthographic detail from Ms. orient. A 432 (gemination in green ink). Photograph taken with a microscope. © Alba Fedeli.